TELDAP Collections

| Bathing Around The World |

|

The first thing a newborn does besides crying is taking a bath. The new baby, eyes closed and wet all over after leaving the mother’s womb, is washed in warm water immediately after birth. The clean, warm feeling is almost as good as being in the mother’s womb.

As we grow older, we develop different bathing routines. Bathing becomes a personal philosophy that only the person who does the bathing knows best and cares about. Some practice all sorts of bathing, from mud baths to hot springs, showering, Turkish baths, saunas, and many more varieties one can enjoy. Some like to add diversity to their bathing experience, having fun exploring different bathing gels and scrubs. These detailed aspects of daily life have been included in the Taiwan e-Learning and Digital Archives Program.

As early as the late Spring and Autumn period, Chinese had already started using a bronze tub, called a jian, for bathing. It was originally a basin with legs, a wide mouth, two handles, and a flat bottom. The container was decorated with cloud, dragon and twisted rope patterns on the outside. Before bronze mirrors became common, a jian might also have been filled with water and used as mirrors. Large-sized jians were used as bathtubs.

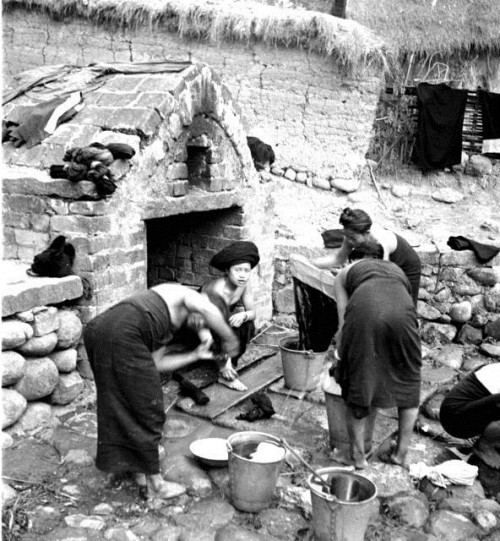

The role of bathing in daily life is reflected in the customs of ethnic minorities in southwest China. The Dai, or Baiyi, people living in Gengma, Yunnan province are highly reliant on public wells. All year round, women bathe at public wells at ease. They only take off their upper garments while keeping their skirts on, which are then changed at home if wet. They bathe in a group and take the opportunity to exchange information, just as urban women might do in the markets.

Baiyi women at a Dai village in Gengma, Yunnan Province bathing by the well.

(Source: Digital Archives of Ethnic Minorities in Southwest China)

Bathing in a bath house can also be very pleasant, and one can take occasion to get the latest news from one’s neighbors. Nevertheless, life-threatening incidents over trivial matters did occur. During QianLong’s rein in the Qing dynasty, fighting in a bathhouse resulted in a fatality and the aggressor was sentenced to be hanged, although the sentence was suspended. During JiaQing’s rein in the Qing dynasty, a man named Chen molested a woman taking a bath with the door ajar in an empty alley. The woman killed herself with poison out of shame and Chen was taken into custody to await the autumn trial, verification, and emperor’s rulikng. Then it would be decided if decapitation would be carried out.

In contemporary times, many hot springs in Taiwan have been quickly developed into public bath houses, both because of Taiwan’s location over earthquake fault and because of the influence of Japanese rule. The public bathing areas in Beitou, Yilan and Caoshan, are all popular relaxation destinations for Taiwanese people.

Interior of a Beitou public bath house in the Taisho period of Japanese rule.

(Source: Taiwan Memory Digital Museum)

Across from the Living Mall in the Songshan district of Taipei city is the Taipei Railway Factory. Constructed under Japanese rule, the factory was where trains were assembled and repaired, and has become the only place where above-ground rail can be found in Taipei. An employee’s bath house was built that utilized steam from the boiler of the factory to heat up water in the bath house. After a hard day, workers covered with grease and dirt could visit the bath house, which operated half an hour before the workers were off duty. After the dirt and fatigue were washed away, the workers could return home refreshed.

This bath house has been recognized by Taipei city as a third-grade historic site. However, the factory will be moved to the Taiwan Railway’s Fugang Base in Taoyuan in 2011. Taipei will lose its last above-ground railway, and the bath house will lose its source of heat. What will become of this historic bath house?

References:

Yin Wei & Ren Mei (2007). The Joy of Bathing. Beijing: China Literary History Press.

Francoise de Bonneville, translated by Guo Changjing (2003). Le Livre Du Bain. Tianjin: Baihua Literature and Art Publishing House.

Yin Wei & Ren Mei (2003). The Chinese Culture of Bathing. Kunming: Yunnan People’s Publishing House.

Items in the Collection:

Previous name: Infant’s bathtub

•Ethnic group: Lukai

•Function: bathing

•Catalog Number: 3624

Wormwood

•Subject and Keywords: Kavalan Tribe; Plants; Wormwood

•Description: Kavalan people add wormwood as spices in rice cake. They also add wormwood in molded rice to make sweet liquor. Using wormwood to bathe can relieve itchiness.

•Identifier: Catalog Number: 9836

|