TELDAP Collections

| The Quest for the River of Gold |

|

The eastern coast of Taiwan is flanked by vast mountains whose summits are perennially shrouded by mist. Off the coast are unfathomable trenches beneath the Pacific Ocean. The topographical variety of the eastern coast, combined with its isolation, has lent mystery to a sundry array of myths and stories. The Creative Comic Collection VII: Stories for the Seventh Lunar Month takes the legendary Turuboan on the eastern coast (also known as the River of Gold during the Age of Discovery) as its background. Drawing on the historical records of the Dutch East India Company, the collection harks back to the first phase of the company’s quest for gold more than 370 years ago and focuses on the adventures of a Dutch military officer named Adriaan.

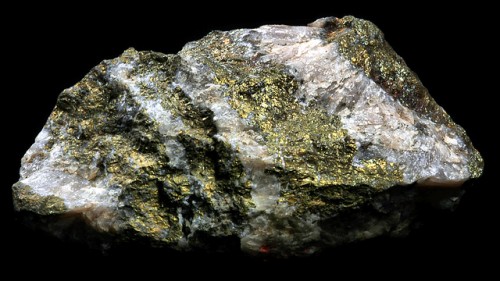

Gold Ore

(Source and owner: Geological Archives Digital Museum, National Taiwan University)

The Dutch East India Company on a Quest for Gold

The Dutch, who traversed the vast oceans before arriving in Tayuan (today’s Anping district, Tainan city), heard from traveling merchants that eastern Taiwan was rich in gold. Legend had it that, tracing the sources of a river called Turuboan, one could discover a mountain of abundant gold ore. Having spent more than a decade building castles, conquering indigenous tribes, and establishing colonial rule in Taiwan, the Dutch began to organize small-scale expeditions. Taking the road from Langciao (today’s Hengchun township, Pingtung county) and bypassing the southern end of the Central Mountain Range, the adventurers headed for Beinan in eastern Taiwan in the hopes of unveiling the River of Gold.

In the first phase of the expeditions, the Danish commercial officer Maerten Weslingh assumed a vital role. According to the records of the Dutch East India Company, Weslingh was a physician, chemist, and oenologist. In 1636, his excellent skills in surgery and winemaking won him the trust of feudal Japan’s government officials; as a result, the Dutch East India Company promoted him to the position of commercial officer and enlisted him in the quest for gold in Taiwan.

In 1638, Weslingh began to establish his headquarters in Beinan and, with the help of local aborigines, traveled northward to the grand Huatung Valley in search of gold. On behalf of the Dutch East India Company, he formed alliances with indigenous tribes in eastern Taiwan, learned their languages, and frequently engaged in investigations in previously undiscovered regions. Records show that he went as far as “four miles from the Spanish city in Keelung” (modern day Heping Island). In light of hostile surroundings and poor traffic conditions, Weslingh’s expeditions were fraught with danger and risk.

The route of Weslingh’s expeditions along Taiwan’s eastern coast.

The End of the Golden Dream

Weslingh’s expeditions, which took him years, did not lead to any clear knowledge of the location of the gold mountain. The samples of gold sent back to Tayuan were scanty, and the only progress seems to have been the unprofitable proliferation of rumors and stories. Weslingh was murdered in 1641 by the aborigines of Tamalakau (today’s Taiping village) and Likavong (today’s Lijia village) in Beinan. What caused the murder, according to local people, was that Weslingh and his companions deserved punishment for having offended an elderly woman. Weslingh’s death set the Dutch East India Company out for revenge, with the governor of Tayuan leading an army to subdue the tribes held responsible for Weslingh’s murder the following year. Due to a lack of successors, the quest for gold was halted, and only after the Spanish forces in northern Taiwan had been driven out did it begin anew.

Following the expulsion of the Spanish forces, the Dutch colonizers – with the assistance of the Japanese, the Spanish, and local aborigines – embarked on a series of southward expeditions from Keelung. They managed to obtain reliable information regarding the specific location of gold, yet the daunting topographical features, traffic and weather proved to be insurmountable obstacles. The adventurers suffered from tempests, shipwrecks, and ill adaptation, and the expeditions were eventually called off after much deliberation. In the end, the Dutch had no choice but to get their gold by trading with local people.

An Unexpected Dimension to the Quest for Gold

In terms of colonial profits, the gold expeditions of Weslingh and the Dutch East India Company came to nothing, but the documents that bear witness to their adventures still survive. These, along with the records of Spain’s relatively short colonization of northern Taiwan, are invaluable accounts of the geographical distribution and the tribal customs of the indigenous tribes in eastern Taiwan. In the 300 years since, the historical materials furnished by these early European adventurers have been carefully preserved, analyzed, translated, and researched by Japanese, Taiwanese, and European scholars. Increasingly known to the general public, these records provide a wealth of details and delineate the contours of Taiwan’s early history.

Neglected Formosa, a seventeenth-century Dutch account of Taiwan

(Source: C. E. S., 't Verwaerloosde Formosa, 1675)

The legend of the River of Gold did not end with the departure of the Dutch colonizers. In the Koxinga period and during the Qing reign, rumors about gold in eastern Taiwan were recorded from time to time: “The Turuboan is rich in gold particles, which can be sifted from sand … The savages mold them into gold sticks and store them in huge tiles. When they have guests, they open the tiles, showing off their gold sticks but not knowing what to do with them.” Eventually, the Qing government, building railways in 1889, stumbled upon gold particles in the Keelung River in Qidu, and later searches further upstream led to the discovery of gold veins in the mountainous area of Jinguashi. Thus began the great era of gold prospecting in Taiwan. The old legends finally proved true, but everything had changed with the passage of time.

References:

Takashi Nakamura. Studies in Taiwan History in the Dutch period. Mi-Cha Wu, Jia-Yin Weng and Hsien-Yao Hsu (translated). Taipei County: Daw Shiang Publishing Co. 1997.

Zeelandia Journals: Volume One. Shu-Sheng Jiang (translated and annotated). Tainan City: Tainan City Government. 2000.

Naojiro Murakami’s Japanese Translation of Batavia Journals: Volume One. Huai Kuo (translated). Taipei City: Historical Research Committee of Taiwan Province. 1970.

Yi-Chang Liu. Aboriginal Cultures and Sustainable Management of National Parks: Human Activities in the Liwu Drainage Basin in Taroko. Hualien County: Taroko National Park Commissioned Report. 2007.

|