TELDAP Collections

| Clothing Styles in Taipei in the 1930s |

|

Taipei City, a relative latecomer in the urbanization history of Taiwan, began its development first in Monga and then in Dadaocheng. After the establishment of the new Taipei Prefecture in the late Qing Dynasty, walls were erected to mark the circumference of Taipei City, which, together with Monga and Dadaocheng were known as the Streets of Three Towns. After the Japanese takeover, Taipei City came under the shrewd management of the Japanese colonial government. In the 1930s, it was basking in the glory of booming industries and commercial activities. As the political and economic hub of Taiwan, and with infrastructure and urban development well ahead of several second-class cities in China and Japan, Taipei City was famous as the “Island Capital.” On the eve of the Taiwan Expo, Taipei City had a de jure population of 280,000, which entitled it to be called the biggest city in Taiwan. Of all the inhabitants, 65% were indigenous Han Chinese, and 29% were Japanese. The cultural characteristics of these two ethnic groups were distinctly different, and so were their traditional costumes. The Western ideas that had been promoted in Japan since the dawn of the Meiji Restoration contributed to the vogue for Western-style military uniforms, suits, and Western-style dresses. Such a trend also rapidly spread to Taiwan. In addition, the streets of Taipei also saw the popularity of the latest Shanghai clothing fashion and hairstyles, which were introduced through books, newspapers, and magazines.

Family photo of a Taiwanese family showing a variety of clothing styles: (in order from left to right) kimono, right-buttoned shirt, front-opening shirt, suit, Western-style children’s dress, school uniform

(Photo sourced from and archived in the Graduate Institute of Anthropology, National Chi Nan University)

As well as embodying the blend of Japanese and Western styles and the fusion of tradition and modernity, Taiwanese clothing, especially that of women, was known for its exquisiteness and craftsmanship, as recorded in historical documents from the Qing Dynasty through the Republic era. Taiwan did not have a prosperous local textile industry, but was active in overseas trading. These two factors caused fabrics in Taiwan to be sourced from the four corners of the world. Taiwanese women were skilled in dressmaking, needlework, and embroidery. Out of doors, they wore traditional costumes which had been innovatively re-designed, such as new qipaos, or Western-style dresses. The variety of clothing often awed first-time visitors of Taipei.

Details about clothes commonly seen on the streets of Taipei in the 1930s will be given as follows:

Short front-opening shirt, long shirt, and riding jacket (male)

The traditional costume of Han males in Taiwan consisted of shirts and trousers, featuring short front-opening shirts, which were easy to put on and take off, for the upper body, and trousers or capri pants for the lower body. Because there was not a great difference between Taiwan’s summer and winter temperatures, the styles of winter and summer clothing were similar, both featuring plain colors or black. In the 1930s, short front-opening shirts were still popular among the lower/working class in the Han settlements in Taipei City. The long shirt and riding jacket were formal costume for Han males when they attended festivals, rituals, and parties. Although they were gradually replaced by suits from the 1920s onwards and became a rarity in ordinary public places, they were still worn for traditional events.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the Graduate Institute of Anthropology, National Chi Nan University)

Right-buttoned shirt (female)

Following the tradition of Fujian and Guangdong provinces, most Han women in Taiwan wore right-buttoned shirts to prevent the revealing of their bosom. The shirt was paired with either a pair of trousers or a skirt and was usually decorated with embroidered borders and patterns, which ranged from flowers, plants, birds and animals to characters denoting fortune/longevity and geometric shapes. Most of the cotton, silk, and woolen threads required in dressmaking were shipped to Taiwan from other parts of the world, hence the wide variety of patterns and colors in Taiwanese clothing. As a general rule of thumb, the clothes worn by women of Fujian descent were more exuberant, while those worn by Hakka women were more rustic. Before the 1910s, the right-buttoned shirt was almost the one and only clothing style of Han women in Taiwan. Whether paired with a skirt or a pair of trousers, it was not an oddity in public places in the 1930s.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the National Museum of History)

Kimono (female)

Kimono, the Japanese traditional garment, originated in the Nara period, during which time kentoshi (imperial ambassadors to the Tang Dynasty) were sent by emperors to China to learn Chinese social systems and culture. As such, the upper class began to adopt the Tang dress code. After a sequence of improvements, the patterns and colors of kimonos became more and more distinctive and dazzling. The present kimono style dates from the Edo period. When out and about, Japanese women, especially those who came to Taiwan in the early days of the Japanese rule, wore traditional kimonos, not only to set themselves apart from the locals but also to mark their privileged position. Taiwanese women only wore kimonos on special occasions, at a wedding or at school for example; otherwise the wearing of the costume was restricted to women working in a limited number of service industries. During the Japanization period, the government once attempted to promote the wearing of kimonos for every woman, but such a campaign was of no avail for reasons such as Taiwan’s hot climate, the high prices of kimonos, and the economizing measures adopted during the war.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the Graduate Institute of Anthropology, National Chi Nan University)

Kimono (male)

The kimono worn by Japanese men originated in the Three Kingdoms period, during which time silk was imported from the Wu Kingdom and used in making garments that resembled the Han Chinese clothes. These earliest kimonos were known as gufuku (clothes of Wu) and worn by ordinary people. In the following years, several stylistic changes took place before the dominant style of modern-day kimonos was finally set, such as the inclusion of a hip- or thigh-length jacket in the Sengoku period and the replacement of the many layered, unlined hirosodes by kosodes (a basic Japanese robe) in the Edo period. During the early days of the Japanese rule, most Japanese wore kimonos, but in later years they were gradually taken over by suits as the primary going-out outfit.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the Graduate Institute of Anthropology, National Chi Nan University)

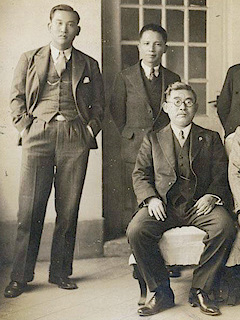

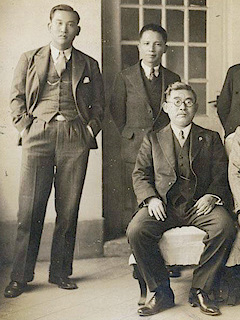

Suits (male)

During the Meiji Restoration, suits were introduced to Japanese society because they were considered to be the embodiment of advanced Western civilization. In China, a general cry for innovation and transformation was prevalent around the Xinhai Revolution. Some businessmen and students returning from overseas began to cut their long braids and swap traditional riding jackets for suits. In Taiwan, suits became more widely accepted in the 1920s. By the early 1930s, suits, shirts, neckties, and hats had been adopted by upper- and middle-class men, whether Taiwanese or Japanese, as standard formal wear.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the National Tsing Hua University Library)

Western-style dress (female)

Western-style clothes first appeared in Yokohama, a port opened for trade in the late Edo period. During the Meiji Restoration, upper-class Japanese gradually opted for Western-style clothing when socializing with Westerners, and a clothing improvement movement was launched to disseminate the convenience and affordability of Western-style clothes in the middle of the Taisho period. As a result, Western dressmaking techniques were actively promoted, and dresses were adopted as women’s uniforms in the wide range of professions that began to be open to women. Such a trend also spread to Taiwan. As shown in photos taken in the late 1930s, it was not uncommon for women working as school teachers, operators, office workers, and factory workers to wear dresses.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the Graduate Institute of Anthropology, National Chi Nan University)

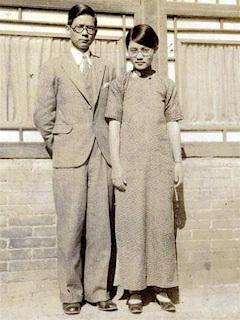

Qipao (female)

Qipao originated from the traditional Manchu costume. Under the influence of the women's liberation movement in the early Republic era, female students in Beijing adopted some of men’s styles. In addition to wearing short hair, some of them began to wear men’s long shirt. Because female students stood for new women in a new era, their clothes became in vogue among women in general. In the 1930s, after the introduction of slits and short sleeves, the more tight-fitting Shanghai qipao soon caught on. As Taiwanese women had never fallen behind in following the latest fashion, these new qipaos soon became commonly seen on the streets of Taipei.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the National Tsing Hua University Library)

Official uniforms (male)

To highlight the majesty of the ruler and facilitate colonial rule, the Japanese colonial government designed its official uniforms based on the style of military uniforms in the West. Civil servants such as officers, policemen, teachers, and rail station workers were ordered to wear uniforms at work. Because government staff abounded in Taipei City, official uniforms were frequently seen in public places and often served as formal wear on important occasions. In the late Japanese rule, official uniforms also became a symbol of prestige for the Taiwanese elites who had newly entered the ruling class. Dr. Du Congming, the first Taiwanese to hold a PhD in medical sciences, and Mr. Wu Zhuoliu, a writer who once worked as a public school teacher, were wearing these uniforms in some of their photos taken in this period.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the Graduate Institute of Anthropology, National Chi Nan University)

School uniform (male)

The Japanese school uniform for male students designed in the Meiji period also had its origins in the military uniforms of the West. It featured a standing collar and a student cap. Pins were used on caps, lapels, or cuffs as decorations and group markers. From the 1920s onwards, the Japanese school uniform for male students began to be widely adopted in Taiwan’s public schools and colleges. Because school uniforms represented the distinction of receiving modern education, Taiwanese young men often attended family gatherings in their school uniforms when they were students.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the Graduate Institute of Anthropology, National Chi Nan University)

School uniform (female)

During the Meiji Restoration, Japan implemented policies of Westernization. To help its people build a healthy body, the government integrated physical education into the school curriculum. Because the traditional kimono was cumbersome as sportswear, certain schools chose the Western-style dress as the outfit for sports activities. The sailor outfit as a uniform for female school students began to catch on in Japan in the early 1920s. It was also adopted in some of the women’s schools and colleges in Taiwan. Graduation photos from this period indicate that each women’s school had its own uniform, and styles ranged from the traditional right-buttoned shirt to the Western-style dress and the sailor uniform.

(Photo sourced from and archived in the Center for the Study of Traditional Arts, Taipei National University of the Arts)

References:

Nakayama, Chiyo. (2010). History of the Dresses of Japanese Women. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

Nagashima, Nobuko. (1943). History of Japanese Costume. Kyoto: Unsodo, Showa.

Editorial Committee of the National Museum of History (Ed.). (1995). The Folk Clothing in Early Taiwan, 1796-1932: Collection of the National Museum of History. Taipei City: National Museum of History.

Ye, Licheng. (2001). History of Taiwanese Costume and Fashion. Taipei City: Shangding.

|