TELDAP Collections

| The Naxi Romeo and Juliet – An Introduction to the Jifeng Rites in the Naxi Scripture Migration of Youth |

|

By Hu Qirui Assistant of the Project of Historical and Cultural Heritages Develped in the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica Foreword It is hard to talk about William Shakespeare without mentioning one of his most well-known works, Romeo and Juliet. In this timeless masterpiece, the two young lovers are forced to tragically sacrifice their lives when the hatred between the two households proves too great a force for their young love to overcome. Coincidentally, the Naxi people of Yunnan Province tell a similar romantic story of how one of a star-crossed lovers committed suicide because of their forbidden love. This story is contained within the scripture Migration of Youth , and is recited by the dongba (priest of Naxi Tribe) to appease the restless spirits of those who have committed suicide for love. Their hope is to help lead the spirits of the dead to lasting peace in the paradise atop the legendary Jade Dragon Mountain. Since the scripture depicts the heaven that awaits faithful lovers after death, it has in some ways encouraged a growing number of young lovers to commit suicide together. Thereafter, the recitation of this scripture was banned, an act that also made the Migration of Youth the most famous scripture among all Naxi ceremonies to appease spirits and quell demons.

Fig. 1 (Right) Dongba of Naxi Tribe

I. What is the Dongba Scripture?

In recent years, tourism in Yunnan area has burgeoned tremendously. Programs that introduce the ethnic minorities in Southwest China have also become commonplace across various media outlets. Guided by these programs and paid tours, tourists have turned Lijiang town into probably one of the most popular vacation spots in Yunnan. In addition to the diverse Naxi music and dance performances, the Dongba Scripture, unique to the Naxi people, has become the main attraction for an increasing number of tourists.

The Dongba Scripture is not a single text, but instead a collection of scriptures used by Naxi priests during religious ceremonies. Since Naxi people call their priest the Dongba, texts written by the dongba are thus known as the Dongba script, and scriptures used by the Dongba refer to the Dongba Scripture.

According to academic research, the Naxi people originally had four writing systems, the Dongba script, the Geba script, the Ranco script and the Masa script. Among these, people today are most familiar with the Dongba script, which is a pictographic writing system. In the Naxi language, this type of pictograph is called “²ss ³dgyu, ²lv ³dgyu ” which translates literally as ”wood and stone records”. Basically, it says to “draw wood if you see wood, draw stone if you see stone,” which leads to a pictographic system1. The Geba script is a syllabic script, and in the Naxi language, Geba means “disciples”. The Geba script uses phonetic symbols, with one character corresponds to one syllable. Although it’s easy to write, the characters of the Geba script do not always follow the same form. The Geba systems may have been developed by Dongba disciples as a way to record the contents of the Dongba Scripture 2. The Dongba script and the Geba script make up the bulk of the Dongba scriptures, while the Ranco script and the Masa script are derivations of the Geba script, and are less commonly seen in the scriptures.

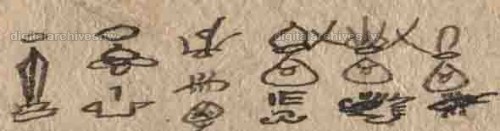

Fig. 2: Example of the Dongba script.

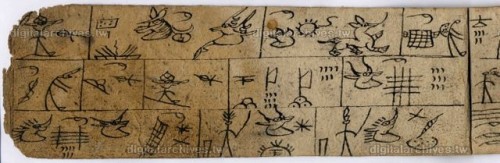

Fig. 3: Example of the Geba script.

The texts of the of Dongba scriptures serve many purposes 3. Some are used to ward off impurities and in ritual offerings, while others appease and propitiate the spirits of the deceased. Some recount beautiful stories, others are used to divine good or bad fortunes. Since the contents of Dongba scripture are rendered mostly in pictographic scripts, it is an interesting read and well-liked by many. At the same time, the Dongba script is one of the few remaining pictographic systems still in use around the world today, and therefore has captivated the academia as well. Some scholars even name it “the living pictograph” 4. So far, a great number of scholars, experts and research institutions have joined in the studies of this fascinating script.

The Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica (hereafter referred to as the Institute), also has a collection of over 370 volumes of Dongba scriptures. Most of these scriptures were collected by researchers of the Institute who in the early days conducted field research in Southwest China between 1935 to 1936. The Institute’s entire collection has now been fully digitalized as part of the “The Project of Historical and Cultural Heritages developed in the Institute of History and Philology, the Fourth Branch: Digital Archives for Ethnological Artifacts, Photos and Scripts”. In the future, the archive will be accessible to all via an online database, providing interested scholars as well as the general public the chance to browse, research, and learn from these valuable resources.

II. Summary of the Migration of Youth 5

The Migration of Youth described in this article refers to the Jifeng Rites, which is a Naxi religious ceremony meant to propitiate various spirits including cloud spirits, wind spirits, spirits of the hanged, spirits born of love suicides, spirits of the poisoned, and various others. The word feng (wind) refers to a collection of supernatural forces represented by the wind spirits. The Naxi people believe that these spirits come both from nature and human society respectively 6. The Jifeng Rite is mainly an offering for “ spirits of nature”, but “spirits of society” are also involved. The Grand Jifeng ceremony, which focuses on propitiating the spirits of the dead, is mainly an offering for “spirits of society”, but “spirits of nature” remain a part of the ceremony.

There are two types of ceremonies, one to propitiate demons and pay back the debt owed to demons, another to propitiate spirits of the dead and pay back the debt owed to demons. The Naxi people believe that if a person suffers an unnatural death, their spirit will be stuck among the world of the living, occupying the same space as the demons of nature. Especially for relatives of the dead, such spirits are often hard to rid of. It falls to a Dongba to protect the family by performing a ceremony which summons these spirits, propitiates both human spirits and the demons that have followed them, pays back the debt owed to the demons, quells them, and eventually sees the spirits off to their dwelling in the afterlife 7.

Therefore, the entire Jifeng ceremony is complex, including “the Jifeng to propitiate spirits of a love suicide” and “the Jifeng to propitiate spirits of unnatural death”, as well as Jifeng ceremonies to resist demons, including the “ceremony to eliminate disaster and illness”, the “ceremony to summon spirits”, and the ceremony of prayer to the gods, i.e. “the ceremony of wishes”8.

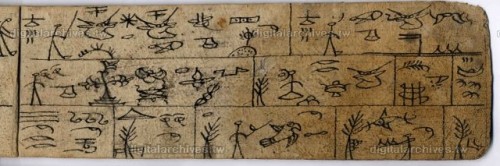

Fig. 4 & 5: Images of the Migration of Youth from the Naxi Dongba Scripture housed by the Institute.

Migration of Youth is known as “lumanlusha (lv bber lv ssaq)” (transliteration) in the Naxi language. The “lv” here means a young male and female, while “bber” and “ssaq” both refer to migration or moving, hence the translation “the migration of youth” 9.

Migration of Youth can be divided into eight parts. The story starts by portraying how in ancient times, all things and beings moved down from a divine mountain called “Junaruoluo” (transliteration). However, the youth refused to migrate with their parents, and sought to abandon their parents by committing a love suicide with the boy or girl they loved. The parents pleaded and petitioned their children, hoping to convince them to take the journey with them. Some parents even traded their great life-span with that of their children, hoping to persuade the young ones to forget their suicidal plans. But their young scions would not easily dissuaded, so the parents had to build fences and gates to keep their children from seeking death.

Trapped inside, the youth found a divine tree and lived for a long time underneath its branches. There they made many beautiful ornaments of the things that fell from the tree. Their captivity and industry form the second part of the story.

In the third part, the youth finally broke through all barriers and escaped. However, those who escaped found many obstacles blocking their continued migration. They waited from winter to spring, summer to fall, but finally, when the season to migrate had again arrived, a flood waylaid them once more. Nevertheless, the youth persisted, eventually overcoming all difficulties and completing the first migration.

However, the first migration did not bring them happiness. The scripture suggests they had too little space to plot their own territories, or were unable to be with their loved ones because in the parents’ eyes, together they would form an unfavorable and unsuitable marriage. Therefore, a second migration took place. Even so, the scripture also mentions that not all the young ones escaped successfully. Some were unable to break through the fences built by their parents, a foreshadowing for the fourth part of the story.

In the fourth part are introduced the hero and heroine of the story: “Zibuyulengpan” and “Kangmeijiomingji” (both transliterations). They began in the very beginning of this part as lovers, and although Kangmeijiomingji was able to follow the other youths into the first migration, Zibuyulengpan could not escape his parents’ prison. Kangmeijiomingji saw that the others all had a mate and only she was alone, so she asked the raven to bring a message to Zibuyulengpan’s parents, petitioning her suit and presenting her as a pure and flawless girl, only in hopes of gaining their permission to free their son and agree to their union. But Zibuyulengpan’s parents were not moved, and stung her with vicious replies. After suffering the attacks of his parents, the young girl was dealt another blow when Zibuyulengpan did not show on the date they had planned because he had to work. Dejected, Kangmeijiomingji began to contemplate suicide. Drawn by her suffering, the demon of love suicide appeared and began seducing the young maid, convincing her that earthly life was filled with nothing but pain and suffering, and only in the afterlife would she be able to exist in peace.

Kamagyumigyki, captivated by the demon of love suicide, tried many times to commit suicide, but each time in vain. Finally, she managed to hang herself, and her death brings the fourth part of the scripture to an end.

One day, Zibuyulengpan went looking for a lost cow and stumbled across Kangmeijiomingji’s cold dead body. The sight of his beloved’s lifeless face brought tears to Zibuyulengpan’s eyes, and he repented. He even communicated with the spirit of Kangmeijiomingji, telling her how much he loved her, hoping to bring her back to life. But he asked the impossible. Kangmeijiomingji wanted Zibuyulengpan to cremate her body so that her spirit might arrive in the paradise for those who committed love suicide, the kingdom where the love suicide demon dwelt. Before she left, she told Zibuyulengpan to retrieve the money she stashed away on earth after waiting a certain span of time. After Zibuyulengpan promised her, he cremated her body.

The beautiful but sad story would have ended here, had Zibuyulengpan but followed the wishes of his lost love. In the sixth part of the Migration of Youth, however, he grew impatient, going to retrieve Kangmeijiomingji’s treasure earlier than he had promised. Therefore, the spirit of Kangmeijiomingji haunted him, and lured away Zibuyulengpan’s soul and spirit. Only the power of a Jifeng ceremony to propitiate spirits and demons could bring Zibuyulengpan back to normal.

The seventh and eighth part reminds contemporary Naxi people various lessons and rules to heed to when making preparation for such ceremonies, so as to ensure families holding the ceremony will no longer be disturbed by these spirits and demons. Only by holding such ceremonies, can these families live “without illness or pain, without surprise or fear, and in harmony with a sound soul.”

III. Closing Remarks– A Controversial Piece of Scripture

As has been mentioned above, though the scripture was originally used to propitiate the spirits of those who committed love suicide, its heart-rending romance and the idyllic afterlife it paints as awaiting lovelorn souls render the Migration of Youth a lure for young men and women to begin committing suicide together. In the end, the more people died in love suicides, the more the scripture was recited, and the more the scripture was recited, the more people committed love suicide. Soon, an epidemic was spreading. In the end, they had to resort to political force and ban the recitation of this scripture. The Dongba scholar Li Lincan said, “If any Dongba dared to conduct such ceremony, merciless imprisonment and interrogation would be faced.” When Li Lincan went to Lijian in 1939, he tried to find a Dongba to recite this scripture for him, but because they were “still intimidated by the aftermath of the policy”, he was refused by all. In the end, he had to find a secluded room to get a Dongba to secretly recite it to him10.

However, just as all pop songs that were banned by political force, this banned scripture became all the more famous and is popular until even now. A scholar once said, “This beautiful mythological tragedy vividly depicts the true love and rebellious spirit between the hero and heroine. Especially with the rendering of the heroine, it was so delicate that one cannot help but shed tears; the language of this work is colorful, graceful and melodious, worth reading over and over again There is wisdom in every sentence. It is yet another triumph of the Naxi literature.” 11 After such high praise, it seems fair to call this the Romeo and Juliet of the Naxi people.

Further Reading:

Recitation of parts of the Migration of Youth of the Naxi People (Recited by: He Limin, Date: June 18, 2005)

“Villages” Website: http://ethno.ihp.sinica.edu.tw/index.htm

Database of Ethnic Minorities of Southwest China:http://ndweb.iis.sinica.edu.tw/race_public/index.htm

Endnotes:

1. Fang, Guoyu, “Comparative Research on Chinese Pictographic Script, Bronze Inscriptions, Seal Script and Naxi Pictograph“, Culture Dongba. Kunming: People’s Publishing House of Yunnan, 1999, pp. 92.

2. Yang, Shengmin, Record of Chinese Nationalities. Beijing: Minzu University of China Publishing House, 2003, pp. 247-48. Regarding the origin of Geba script, Li Lincan held a different opinion. For a detailed discussion and full introduction, please see Li, Lincan’s Naxi Pictographs and Phonetic ScriptDictionary. Kunming: People’s Publishing House of Yunnan, 2001, pp. 427- 29.

3. The total number of Naxi Dongba scriptures remains undetermined. Early researchers believed that there were 528 volumes, but after sorting, classification and statistics, the number at present runs to one thousand volumes. See Lin Xiangxiao’s “Dongba Scripture and Ancient Naxi Culture”,.Culture Dongba, pp. 15.

4. He, Wanbao, “Preface”, Culture Dongba, pp. 4.

5. Citations of the Migration of Youth included in this article are based on the Longbalusha (Lijiang) Volume II (Shelf mMark: MS-181) housed by the Institute, translated by Mr. He Limin, adapted and revised by the author, and the author is responsible for any mistakes made.

6. For example, the cloud and wind spirit mentioned above are spirits from nature, whereas hanged spirit and love suicide spirit are demons from human society.

7. Record of interview with He Limin, August 22, 2006.

8. He, Limin, Introduction of to the Naxi Dongba Ji-feng Rites) (unpublished).

9. Dongba Culture Research Center Ed., ”Grand Ji-feng– Lubanlurao“, An Annotate Collection of Ancient Naxi Dongba Texts, vol. 83. Kunming: People’s Publishing House of Yunnan, 1999-2000, pp. 108. The author transliterated this scripture as “Lubanlurao, early transliteration by the Institute was “Longbalusha” and now “Lumanlusha”, thus unifying the transliteration hereafter.

10. Li, Lincan, “Stories on the Moso Tribe”, Collected Essays of Moso Research. Taipei: National Palace Museum, 1984, pp.300.

11. Yang, Shiguang, “On Dongba Literature of the Naxi People“, Culture Dongba, pp. 340-41.

|