TELDAP Collections

| The Chronicles of Taiwanese Vernacular Literature |

|

By Chen Taiying

Digital Archive and Learning e-Paper

Project Assistant and News Editor

An Alternative Window on the Island’s History

Taiwanese culture is composed of a diversity of peoples, and its destiny is strikingly analogous to the natural geological features of the island: young and prone to earthquakes and typhoons. The alternating process of destruction and construction seems to be the core of Taiwanese identity. Because of this fateful cycle of history, a strong sense of uncertainty and restlessness haunts the minds of the islanders. Diverse cultures should coexist in harmony, cherishing each others’ languages and cultures. However, under political turbulence, languages and cultures become memorial statues that were demolished or erected along the great tides of history.

How can cultures be compared in terms of superiority? For most of the 20th century, Taiwanese, the most widely-spoken language in Taiwan, has been labelled by various conquerors as a crude dialect, negating the possibility of language enrichment in public and academic spheres. However, what is the reality of the linguistic culture of Taiwan? Through the Taiwan Church News Vernacular Literature Digital Archive Project, Li Chin-An, Professor and Chair of the Graduate Institute of Taiwan Culture, Languages and Literature, National Taiwan Normal University, is offering readers a new historical perspective on the development of the linguistic culture of Taiwan.

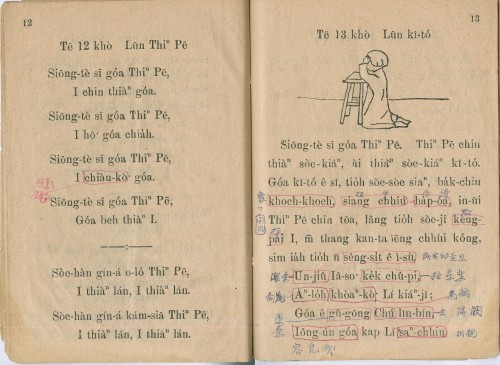

Mr. Yang Yun-Ping makes hand-written remarks in this Basic Reader.

Origins of Vernacular Taiwanese

According to ethnologists, the written word of the Amis, Bunun, and Puyuma peoples had once existed but had been lost. Abstract symbols have also been found on wooden calendars for recording agricultural timings and seasonal rituals in the Bunun tradition. Nevertheless, before the Dutch introduced the Romanization system in the 17th century, most historical records about aboriginal peoples were found in the writings of cultures with long literary traditions, such as China, Japan, and Korea. Besides the gospels, the Dutch missionaries also introduced the phonics writing system to the locals of the Pinpu Xingang tribe. This writing system was used not only for reading the Bible but also for making written agreements with the Han people from mainland China. The Dutch left Taiwan after Zheng Chenggong’s military victory over the East India Company in 1662, but this Church Romanization writing system (called Pe̍h-ōe-jī) stayed, chronicling the lives of the people of Xingang tribe in Tainan until 1813.

Zheng Chenggong and the Qing dynasty of China transformed “Formosa” to “Taiwan,” not only drawing Taiwan closer to the mainland in terms of territorial sovereignty, but also bringing about drastic structural changes to the development of Taiwanese society. The Han immigrants flocked to Taiwan from southern China, bringing strong cultural influences and assimilating the local aboriginal people. In one of the Genre Paintings of the Austronesian Societies, archived in the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, the image of Pingpu children reading Confucian classics at a straw house insinuates the diminishing of the aboriginal traditions and Dutch influences. Under the impact of Han Chinese, most people in Taiwan retained little attachment to the legacy of the Church Romanization writing system.

When the Christian church re-emerged in southern China and Taiwan in the 19th century, the missionaries preached using the Church Romanization writing system as had their predecessors; however, the Han societies they confronted at that time were highly diverse in terms of language and script. Officials and the elite class utilized Mandarin and classical script, whereas the illiterate masses spoke in vernacular languages and grassroots dialects. When the missionaries targeted the masses in their gospel messages, the systematic phonics approach of Church Romanization became the best tool for overcoming the language barriers between the preacher and those preached to. After all, there are as many as 1,000 common Chinese characters, but no more than 30 Roman letters in an alphabet. After mastering the alphabet, anyone, including uneducated females, would be able to spell out any linguistic sounds. There were anecdotes where children thought their grandmothers were reading English when they were actually reading the Roman alphabet.

The first printing machine in Taiwan

Taiwanese Vernacular Script: A Historical Testimony

In 1885, Canadian Pastor Barclay founded the Taiwan Prefectural City Church News (later the Taiwan Church News) in Tainan. Printed in accessible vernacular script, it was the first news media with a contemporary perspective. Professor Li Chin-An mentions that, through this earliest, hundred-year-old media, we are now able to gain a local perspective in exploring the concerns of Tainan’s Han Chinese and Presbyterian Church communities. For example, issues of tariff commerce and the provincialization of Taiwan were discussed using vernacular script in the report entitled “Taiwan is Going to be a Province” in June 1886.

The year of 1895 marked a crucial year in the history of Taiwan as the Qing Dynasty signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki with Taiwan. In a down-to-earth tone, the Taiwan Church News reported in May the contents of the treaty: “Taiwan is given to it, Penghu is given to it”. Although this article confirmed that the Japanese government provided a term ensuring the freedom of nationality choice, legitimate according to modern international law, the pains of separating from the motherland impacted strongly in most readers at the time of pre-modernized Taiwanese society. Therefore, in June, the Taiwan Church News published the announcement of the military leader of the Republic of Formosa, General Liu Yongfu, imploring citizens and elites to curb their hatred towards other foreign nations and to conform with the Republic of Formosa’s diplomatic strategy of confirming diplomatic ties and waiting for international aid: “All the gents, businessmen, soldiers, and the public please understand that except for Japan all other Western nations have good relations with us.”

Sadly, Japanese military still overwhelmed the Taiwanese resistance. Professor Li laments that after Liu Yongfu escaped to China on the brink of defeat, Pastor Barclay, on behalf of the local elites, risked entering the military base of Nogi Maresuke, a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, to urge the Japanese military to enter Tainan and to restore order. Thus, military resistance ended and a new era began. To the general public, daily life must continue. In the Taiwan Church News of 1896, policy propaganda such as “Legitimizing the Meiji Regime” from the Taiwan Governor-General’s Office appeared. Articles such as “Fundamentals of Japanese Language” were also published. During the Boxer Rebellion and Eight-Nation Alliance of 1900, the Taiwan Church News provided comprehensive coverage on northern China and the diplomatic impacts of the battle on either side. The vernacular script of the church not only faithfully recorded important events, but also helped to enrich the knowledge and the minds of the readers.

Chronicling Cultural Diversity

Because of the ready accessibility of Taiwanese vernacular script to even the uneducated, a rich collection of secular literature and religious writings could be found in publications such as the Taiwan Church News and Mustard Seed. However, the public still only recognizes the writings of Lai He and Zhang Wojun in classical script as the mainstream of Taiwanese modern literature. This impression, according to Professor Li, is due to the “National Language (Japanese) Policy” promoted by the Japanese government, preventing the vernacular script from continuing to flourish. Taiwanese elites of the 1910s and 1920s realized that armed resistance could not liberate Taiwan from being colonized, so they began to stimulate the Taiwanese nationalistic awareness through cultural movements, parliament-approved petitions, and other peaceful methods. In 1924, Mr. Cai Peihuo planned to offer vernacular script courses on a large scale in hopes of equipping every Taiwanese with literacy. His efforts were, of course, unwelcomed by the Japanese government. The Han Chinese favored classical Chinese script; on the other hand, many Taiwanese youths stimulated by academic thoughts after China’s May Fourth Movement or influenced by the colonizer Japan’s modern literature and social thoughts also chose to read and write in Chinese or Japanese rather than using the script of their own mother tongue. The Christian church was viewed as an enemy by the Japanese during the Pacific War, and the Taiwan Church News ceased publication, adding to the difficulty of promoting vernacular script.

After the Pacific War ended in 1945, the Nationalist Government took over Taiwan. Taiwan Church News resumed publication, but the Taiwanese people were trapped in an awkward circumstance of being colonized by their own nation. The Nationalist Government emphasized the 5,000 years of Chinese cultural traditions, marginalizing dialects including Austronesian or Han. Under the pressures of the Nationalist Government, the clergy were required to preach in Mandarin, and the Taiwanese vernacular version of the Taiwan Church News officially ended on government orders in 1969.

Archived resources might have ended in 1969, but the Bible says: “Unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains just a grain of wheat. But if it dies, it produces much fruit.” Taiwanese vernacular script lost its voice with the demise of the Taiwan Church News, but it still played an important role in connecting overseas Taiwanese and in strengthening Taiwanese cultural identity. The 1990s witnessed the emergence of the localization movement. Various mother tongues regained recognition in public discourse. Taiwanese vernacular script also became more secularized, adopted by many people concerned with the heritage of mother tongues.

Taiwan, Ilha Formosa, has developed a unique cultural landscape where cultural diversity is rooted. Professor Li, as an author and advocate of Taiwanese vernacular literature, speaks in fluent and elegant Taiwanese about the future of the vernacular script in the digital archive program. In his opinion, Taiwanese vernacular script should be a cultural heritage shared across Taiwanese society. Therefore, the results of this digital archive project should be published under the Creative Commons License. From 2008 to 2009, the project team has already translated over 3,000 Taiwanese vernacular articles into both Chinese characters and Romanization, acquired 225 authorized digital images from various agencies, and cooperated with National Taiwan University to scan and digitally archive Taiwanese vernacular collections of the National Taiwan University Library. Now, these digitally archived results can be found on the “Archive of Taiwanese Vernacular Script” website, accessible to the public. The website is well-organized, classifying the catalogue into years, subjects, and authors, facilitating the efforts of readers and researchers in carrying out their studies.

Professor Li wishes to further promote to wider and international audiences this online archive of the Taiwanese vernacular script, along with the permeability of Web2.0 and the accessibility of the Romanization system, allowing the beauty and the diversity of the Taiwanese languages to be appreciated beyond national borders. Even though the vernacular script found in Taiwan Church News ceased to circulate widely, its existence, which has chronicled the meeting points of different cultures, remains an important witness to the history of Taiwan as well as a key to connect the past, present, and future. Through the digital archive project of the Taiwanese vernacular scripts, we not only gain a glimpse of the Taiwanese minds a century ago, but also may create heart-felt literary works with the languages of our mothers. Perhaps a popular Taiwanese quote from the 1990s can reflect this determined and elegant state of mind: “Sweet potatoes do not fear disintegrating into soil, as long as their leaves flourish generation after generation.”

|