TELDAP Collections

| The Cultural Significance of Snuff Bottles |

|

Author: Chen Jialin (Researcher, National Museum of History) Snuff bottles were used by the Chinese to contain powdered tobacco. They can be traced back to the end of the Ming Dynasty and the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, when legates from Europe presented gifts to the Chinese court. After the introduction of snuff bottles into China, the Manchu people in Beijing, who placed a high premium on leisure and entertainment, made snuff-taking immensely popular, both for the court and the common people. Absorbing distinctively Asian elements, snuff bottles soon became fashionable in China. As the progeny of a consummate combination of innovative Western invention and ingenious Chinese craftsmanship, snuff bottles were, and still are, representative antiques that bear witness to the mixture of Asian and Western cultures in the Qing royal court. Since then, they have developed into a unique branch of Chinese art. Snuff bottles were treasured and appreciated at that time and even became symbols of fashion and social status. Meanwhile, however, the original practical use of snuff bottles came to be overlooked, and they were transformed into works of art that assumed vital roles in the gift-giving custom among political figures, in court culture, in entertainment, and in connoisseurship—hence the inexorable development and the vast flourishing of snuff bottles around the time of the culmination of the Qing Dynasty.

The use of snuff, rather than being an indigenous Chinese practice, was a fashionable practice introduced by the West. Snuff was regarded as an expensive present, and the bottles invented for the use of snuff, absorbing both Western and Asian features, followed a unique course of development—a process that witnessed the impact of exotic fashion upon local practices and had multi-faceted cultural significance. Such cultural significance, to be more specific, was born in the historical context of East-West cultural interaction in which the Chinese people learned from the West. Snuff bottles, which of all the works of art in the Qing Dynasty most pertinently convey the cultural significance of this East-West interaction, were thus brought into existence in this period. In the context of cross-cultural interaction, snuff bottles constitute a perfect proof of “Western learning for Chinese application.”

Upon its introduction into China, snuff won the favor of the emperors, who learned how to use it from missionaries and made snuff-taking a daily habit. From Kangxi onwards, the Chinese emperors began to take snuff, and this practice was soon followed by others, becoming eminently popular in the Chinese capital and spreading even to the common folk. The popularization of snuff-taking seems to indicate that Chinese people had to a certain extent renounced the isolationist policy and commenced to adopt a more open attitude towards Western culture. This also led to the rapid development of the snuff-bottle industry during the prosperous period of the Qing Dynasty.

The Emperor Kangxi, who was very particular about snuff bottles, bade the Imperial Household Department set up an institution for the invention and manufacture of snuff bottles. In addition to enlisting craftsmen from the general public to serve for royal purposes in capital ateliers, the Imperial Household Department also employed Jesuit missionaries who brought with them the techniques of glass and enamel production, enamel coloring, and so on. As a result, the mid-18th century Rococo style, with its exquisite ornamentation and extravagant court craftsmanship, was instilled into the Chinese art industry, exerting a profound impact on Qing decorative arts.1 This confluence of technical skills, brought about by both Chinese and foreign craftsmen, also exemplifies the East-West interaction at that time. The snuff-bottle industry was already independent in the Yongzheng period. This new and prosperous stage of craftsmanship witnessed the transition from the imitation of the Western use of snuff boxes to the development of a style of its own. In the Qianlong period, the production of snuff bottles incorporated still more exuberant subjects and techniques. Snuff bottles were originally made of glass, and those that were made of porcelain, jade, metal, bone, shell, plant, etc., gradually appeared. The craftsmen were adept at utilizing such techniques as burnishing, sculpting, painting, and calligraphy on petit bottles—producing, for example, amazingly carved glass with multilayer colors, exquisite and delicate porcelain with painted patterns, jade with warm luster, agate in wondrous natural forms, intricate and beautiful enamel, and meticulous inner paintings (paintings inside glass spheres or snuff bottles). These came in all varieties of huge, small, square, and round forms while their decorated patterns were pregnant with Chinese culture—traditional concepts, tales, myths, thoughts of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, and auspicious meanings, thus bestowing a unique artistic value on Chinese snuff bottles. Such new techniques resulting from the merging of Chinese and Western elements supplied a new dimension to Chinese craftsmanship, and the refined artistic skills far excelled those of the West.

In addition to their practical use, snuff bottles were regarded as precious gifts for friends and relatives and were exchanged for aesthetic appreciation during casual rendezvous, cementing interpersonal ties. As a result, the original practical function of snuff bottles seemed to become overlooked, and they were turned into works of art that served the purposes of presenting political rewards, buying official titles, and of recreation or amusement. This indeed yielded a certain influence on the Qing feudal system and also displayed the repercussions of Chinese people’s acceptance of Western culture during the Qing Dynasty. In the Yongzheng and Qianlong periods, snuff bottles were produced on a large scale, to serve as presents for princes and nobles and as fashionable playthings among high-ranking officials and the emperors’ concubines. According to extant records, Qing emperors such as Yongzheng and Qianlong all selected elaborate snuff bottles for personal amusement or as rewards for their subordinates: “In the 22nd year of Qianlong, the Empress Xiao Sheng Xian went on an inspection tour to the south and presented a snuff bottle to the Huiji Temple in Huaibei.” “In the 52nd of Qianlong, the Emperor bestowed upon the king of Annam two jars of snuff and a snuff bottle.” “In the 53rd year of Qianlong, another three jars of snuff and two snuff bottles were bestowed on the king of Joseon (in Korea), a can of snuff on the king of Lan Xang (in Laos), and on the king of Burma, a porcelain snuff bottle.”2 The book Yong Lu Xian Jie also states, “In the 7th year of Jiaqing, the emissary from Joseon was presented with a glass snuff bottle during a feast in the Chonghua Palace, which later became a custom.”3 It is thus clear that, from the culmination of the Qing Dynasty onwards, snuff bottles became an integral part of the royal practice of gift giving, and its significance for the emperors is evident.

The Qing Dynasty saw itself as a sacrosanct country that possessed the highest power. Within this old regime, Sino-foreign relations were not based on equity; accordingly, a tribute system was established to sustain ties between China and foreign regions. After the introduction and absorption of Western techniques, the Qing emperors, who were keen on bestowing gifts, made it a custom to present snuff bottles to emissaries from far away, in return for tributes from foreign kings, flaunting the majestic power of China. The Documents Concerning the Relations between the Kangxi Court and the Papal Legates, issued by the Imperial Household Department, states, “December 5, the 59th year of Kangxi, the Western legate Jean Ambrose Charles Mezzabarba paid tribute with presents from the Pope. The Emperor gave him as gifts a snuff bottle, a small bag that contained flint and steel, and four embroidered pouches…”4 Thus, snuff bottles were looked upon as important presents in the context of international interaction. Throughout the Qing Dynasty, snuff bottles assumed a mediatory role in the exchange between China and foreign countries; in the meantime, to Westerners, they also served as a window on Chinese culture. Bestowing Chinese-style snuff bottles in return for Western tributes, the emperors brought the image of the Qing Dynasty as a divinely ordained empire to the fore.

Snuff bottles played an important role in the diplomatic and bureaucratic gift-giving custom of the Qing Dynasty, forming a bridge of friendship between China and the West. From another perspective, however, they reflect China’s Sino-centered worldview at that time, which relegated the West to the uncivilized periphery. Therefore, facing the inexorable influx of Western technology and culture, the Emperor Yongzheng adopted Western knowledge for Chinese practice though, he limited this to personal recreation and amusement and did not further develop the knowledge. The Emperor Qianlong even regarded Western knowledge as a trifling skill. On the whole, the Qing emperors, though influenced by Western culture and taking the first steps to learn from Western culture, went nowhere but indulged in watching and toying with novel and ingenious Western inventions. Not realizing the remarkable power behind these inventions, they continued to be intoxicated by the dream of being the rightful center of the world, to emphasize the humanities and ignore technological development, and to hinder China from being transformed into an industrial country—a parochial mindset that brought about devastating results. This is one of the most regrettable parts of the history of East-West interaction. During the transition from the Qing Dynasty to the Republic Era, the practice of snuff-taking went into a decline, and snuff bottles were gradually replaced by tobacco, hookah and cigarettes, making its exit from the stage of history along with the Qing Dynasty.

Having inherited the snuff bottle—a kind of “Western gadget”—from Europe in the 17th century, Chinese artisans continued to incorporate new artistic techniques under the enthusiastic support of Yongzheng and Qianlong. They made snuff bottles a mixed product of Western and Chinese cultures and finally established a distinct Chinese style. The development of Chinese snuff bottles can be said to constitute the best example of East-West cultural interaction, taking on profound cultural significance. The convoluted and laborious path of the development of Chinese snuff bottles clearly demonstrates the many social and cultural facets of China in its accepting the West and learning from it: the formation of a leisure culture and enjoyment of artifacts, the cooperation and interaction of Chinese and Western artisans, the new style of Chinese art, the gift-giving custom between emperors and their lieges and among officials in the feudal system, the give and take between the Qing court and the foreign countries, and the decline of a country that saw itself as a divinely ordained empire and relegated the West to a barbarous periphery.

In the history of Chinese arts and crafts, snuff bottles occupy the span from the Wanli period in the late Ming Dynasty to the beginning of the Republic Era. Although the history of snuff bottles only lasted four hundred years, they brought about such practices as political rewarding, gift-giving, buying official titles, amusement of art, recreation, and so forth, in the political, social, cultural, and psychological spheres of the Qing Dynasty. The mixture of Chinese and Western cultures as revealed in the forms, styles, patterns, and skills of snuff bottles infused a refreshing air into Qing art, exhibiting the features of this cultural mergence and the highly refined material culture of 17th and 18th-century China. The cultural significance of snuff bottles can never be equaled by that of other Chinese artifacts.

1 Zhang, Fuye (張夫也). History of Foreign Arts and Crafts (外國工藝美術史). 1st ed. Peking: Central Compilation & Translation Press, 1999. 452.

2 Zhou, Zhiqian (趙之謙). “Yong Lu Xian Jie” (勇盧閒詰). Works on Art (美術叢書). Vol. 3. Ed. Huang, Binhong (黃賓虹) and Deng, Shi (鄧實). Taipei: Yee Wen Publishing Company, 1947. 202-203.

3 Ibid. 203.

4 Chen, Yuan (陳垣), ed. Documents Concerning the Relations between the Kangxi Court and the Papal Legates (photocopy) (康熙朝與羅馬教皇使節關係文書). National Palace Museum of Peiping, 1932. 11.

5 Cornforth, Trevor, and Nathan Cheung. Chinese Snuff Bottles. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2002. 15.

Related Collection

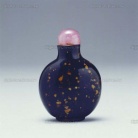

Blue Glass Snuff Bottle with Golden Spots (Registration No. 8195)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8195

Crimson Glass Snuff Bottle with Two Hornless Dragons (Registration No. 8196)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8196

Sesame-Colored Glass Snuff Bottle with Green Lotus Flowers (Registration No. 8197)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8197

Snuff Bottle in the Color of Lotus Root with Crimson Hornless Dragons (Registration No. 8198)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8198

Reddish-Mauve Snuff Bottle (Registration No. 8199)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8199

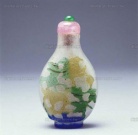

Glass Snuff Bottle in the Color of Lotus Root with Seasonal Flowers (Registration No. 8200)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8200

Black Snuff Bottle with Golden Leaves (Registration No. 8201)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8201

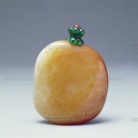

White and Russet Jade Snuff Bottle (Registration No. 8202)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8202

Light Green Snuff Bottle with Grass Insects (Registration No. 8203)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8203

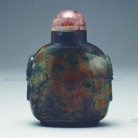

Dark Green Snuff Bottle (Registration No. 8329)

Identification Number: Registration No. 8329

|