TELDAP Collections

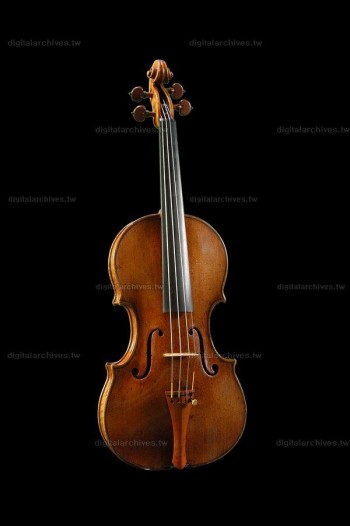

| Chi Mei Museum Violin Collection |

|

Violins of the World – Chi Mei Museum Violin Collection Author: Huang Bixuan / 2009 Digital Archive Learning Bridge Project Collection Story Competition Honorable Mention

Taiwanese violin authority Lee Shude just celebrated her eightieth birthday in the National Concert Hall. Her students, including world-renowned solo virtuosos Lin Zhaoliang, Hu Naiyuan, and a group of budding young violinists gathered together to celebrate the birthday of this living national treasure. Four hundred years ago, no one in Taiwan could have imagined that all the way across the world, in Italy, luthiers were crafting musical instruments that would one day arrive in Taiwan and create such beautiful music.

Violins evolved from a bowed string instrument whose function was to accompany dances in Medieval Europe. The improved version of the instrument emerged in the sixteenth century so that professional musicians could perform in more refined social settings. The advancement ignited a trend for the European aristocracy to learn the violin. At the dawn of the seventeenth century, a new musical aesthetic swept the European continent. Soloists broke free from the longstanding restrictions of the Medieval Church. With their brilliant virtuosity and passionate emotional expression, soloists mesmerized a huge number of supporters. Whether in solo performance or in orchestras, violins became increasingly important. The increased demand marked the time when the craftsmanship of violin-making reached its peak.

The shape of the modern violin emerged from two cities in northern Italy: Brescia and Cremona. Prior to the 16th century, Brescia, situated in Lombardy district in Northern Italy, was already famous across Europe for its choirs, string instruments, and organs. At the beginning of the 16th century, Zanetto Micheli da Montichiaro (1489-1561),the first notable luthier in the Brescian school of violin-making, initiated the city Brescia to its long career of violin-making. In the following hundred years, in the hands of Zanetto’s sons, colleagues, and students, the Brescian school became increasingly sophisticated in its craftsmanship. In particular, the outstanding luthier Giovanni Paolo Maggini (1580-1630/ 1631) upgraded Brescia as the center of violin-making throughout Europe.

Also situated in Lombardy, Cremona did not produce violins until the 1520’s. The legend says that it was after luthier Andrea Amati (1505-1577) moved from Brescia and opened a studio in Cremona that marked the beginning of Cremona’s violin-making empire. However, other sources indicate that Andrea Amati was actually born in Cremona. Apart from the controversy about his background, Andrea Amati was known for founding the Cremona school. His achievements in violin-making made the Cremona school almost synonymous to his family name Amati. The Amati violins are characterized by a mathematically proportioned body and a vibrant amber varnish. Some people believed that these characteristics were the main reason that Andrea Amati could take the lead in making such high-quality violins.

After Andrea Amati’s death, his two sons Antonio Amati (born ca. 1550) and Girolamo Amati (1551-1635) took over his craftsmanship and studio. They also trained apprentices and each opened his own studio. However, just as their businesses were launching, the wars of 1628-1630 followed by the plague and famine, severely damaged the development of violin-making in northern Italy. Many luthiers lost their lives, taking with them their excellent craftsmanship. One such example is the Brescian luthier Maggini. His death brought an end to the Brescian school of violin-making.

One of the few Cremona luthiers who survived was Girolamo Amati’s son Nicolo Amati (1596-1684).Endowed with a good craftsmanship of violin-making, and by training many outstanding apprentices, Nicolo Amati led Cremona’s violin-making to new heights. The previous two generations of Amati luthiers only trained a few apprentices to prevent the spread of their exclusive skills. Because of the fame of the previous two generations, Amati Studio received numerous orders. The lack of manpower and the many luthiers who admired Nicolo prompted Nicolo to accept numerous apprentices. At any given time, Nicolo had at least sixteen apprentices following him and learning his practices. Many outstanding students became important masters, whose names are still well-known today in the development of the modern violin: Andrea Guarneri (1626-1698), Francesco Ruggeri (1620-1698), and Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737).

Nicolo was the most eminent luthier of the Amati family. His most important legacy was revising a standard size for the violin, called the Grand Pattern, also known as Grand Amati. Before Nicolo’s Grand Pattern, violins were differentiated as large violins and violins. When touring around Europe, Charles IX of France (1550-1574) and his mother Catherine de’ Medici once placed orders to Nicolo’s grandfather Andrea Amati for 38 violins, including 12 large violins and 12 violins. The orchestra 24 Violon du Roi of King Louis XIII of France also ordered a few violins from Nicolo Amati. The Grand Amati had a slightly longer pegbox that allows the violin to produce greater volumes. The body length was also slightly extended to almost the size of the modern violin. Thus, the Grand Amati can be described as the precedent of modern violins. Nicolo’s modification, the “Grand Amati” was well- proportioned and elegant. The tone was sweet, the sound could be easily produced, and the volume was rich and powerful. This modification complied with the aesthetics of seventeenth-century Europe, during which individual emotional expression was highly valued.

In 1991, Chi Mei Museum purchased a 1656 Nicolo Amati violin that had once traveled to Brandenburg. Still in very good condition, it has a clear and brilliant tone, and was one of the templates for the Grand Amati. Each of these templates, with some refinement of the details, was used to create the famous 1656 King Louis XIV violin. Nicolo’s Grand Amati elevated the standards of violin-making to another level.

Cremona’s violin-making business began to decline in the 1760s, after the deaths of Stradivari and Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu (1698-1744). The reason for the decline was largely due to the political and economic instability in northern Italy in the eighteenth century. Because of the Grand Pattern, the number of masterpieces of the previous generation became overwhelming and dampened the interest for new orders. After the Industrial Revolution, apprenticeship in traditional violin-making also waned. The rise of the violin enterprise in Germany also contributed to the decline of Italian handmade violins. With the passage of time, many legendary violins became victims of neglect and ignorance. It was not until the early 19th century that violin virtuosos finally unleashed the potential of Stradivari and Guarneri violins, and the famous violins were then restored to their full value. Violins of Brescia and Cremona were endowed with the same value as antiques. The legendary violins that have been played by different virtuosi over the years reflected their history with their glorious tone.

Over the years, Chi Mei Culture Foundation has promoted the development of art in Taiwan. Since the beginning of its violin collection in 1990, Chi Mei Museum has aimed to collect violins from each legendary luthier of each violin-making school throughout Europe. Their ideal is to construct a “violin kingdom” which will end the wanderings of hundreds of violins, allowing them to shine collectively in the same time and space. Since 2006, Chi Mei Museum has been collaborating with the Graduate Institute of Ethnomusicology at National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU) in the endeavor to digitize the violin collection of the museum so the public can view this world-class collection on the Internet. Furthermore, nationally renowned soloists have been invited to collaborate and record classic violin masterpieces to reserve the sounds of the violins. The digitized results are available for viewing and listening on the Chi-Mei Violin Digital Archive Program website.

Reference:

1. Chi-Mei Violin Digital Archive Program Website

2. Music Digital Archive Center, NTNU

3. Cozio.com- Identification and pricing information about old stringed instruments

4. Henley, William. Universal Dictionary of Violin Makers and Bows. Edited by Cyril Woodcock. Brighton, Eng.: Amati Publishing (1973).

5. Medici violins – Linking Artist and Patrons

6. Roberto Regazzi. "Amati, Dom Nicolo." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/00738 (accessed November 23, 2009).

7. Kolneder, Walter. The Amadeus Book of the Violin. Translated and Edited by Reinhard G. Pauly. Portland: Amadeus Press (2001 printing).

|