TELDAP Collections

| National Museum of History—Zhang Daqian’s Lotus Masterpieces |

|

National Museum of History—Zhang Daqian’s Lotus Masterpieces Author: Ba Dong (Chief of Research Division, National Museum of History)

I.Preamble

The National Museum of History in Taipei has compiled a bountiful and vital collection of approximately 150 pieces of works by the contemporary Chinese painting master Zhang Daqian (1899-1983). The National Digital Archives Program recognizes the value of Zhang’s paintings and has selected them for digital preservation. Two of his ink paintings of lotuses are of particular note and therefore deserve detailed introduction. They are “Lotus on Large Screen” (1945) and the ink scroll painting “Gentle Fragrance at Water Hall” (1962). Completed nearly two decades apart, they are ideal examples to show two styles from two different stages of the master’s artistic career.

Zhang Daqian was a well-rounded painter, fully versed in all painting styles and subject matter. His floral paintings are unique and brilliant, and yet attracted little attention as they were eclipsed by his overwhelming reputation for portraits and splash-color style. The main reason for his outstanding achievements in floral painting was because of his wealth of accumulated skills and experience. Over the course of his life he executed countless Gongbi Paintings (Gongbi: a technique marked by meticulous brushwork), traveled far and wide, saw mountains big and small, rivers long and short, and painted grand and imposing landscapes. With such a rich background, he could portray still life with ease, painting with smooth and effortless strokes. At the same time, he deeply admired the beauty of flowers and observed them carefully. When painting a flower he always gave himself totally to the work, enabling him to fully put his craftsmanship and knowledge to use. Thus, by his hand even a tiny piece of floral painting radiates incomparable artistic beauty.

He had a special fondness for the lotus; therefore, the lotus became a principle staple of his artistic creations. One of his remarkable talents was to create gigantic paintings, considered the greatest challenge by many artists. A painting of such daunting magnitude would be impossible for an artist of lesser stamina and artistic mastery. Furthermore, without sufficient forethought and consideration, one would never be able to execute such large paintings. During his life, Zhang did many huge paintings of the lotus, but only two exceeded three meters in height and six meters in width. The “Lotus on Large Screen,” kept in the National Museum of History, is one of those.

II. Zhang Daqian’s Large Scale Lotus Paintings

The sheer size and magnificence of this masterpiece is unprecedented. It is quite possibly the biggest known lotus painting in the history of art. The ink color was applied in layers, dense but not stagnant. The elements in the composition are intimately linked, nowhere losing focus or becoming smothering. Big floral paintings easily become ornate and trivial, and it is extremely difficult to maintain balance and stylistic coherence. This masterpiece, however, despite its enormous size, is still well-organized. Within magnificence unfolds delicate tenderness; the result of the integration of his early scholar-painter style and commitment to elegant, smooth brush strokes. This work is truly a rarity among art, past or present. For one thing, Zhang vividly portrays the lotuses growing in nature, swaying in the summer breeze, and casting shade in the heat of summer. For another, he magically personifies the flowers, conferring upon them a stately grandeur.

The verse on the painting reads: “A flower, a leaf, and the west wind; Big Di, did you know this then do you know well the scene? In the flower a home I would make, yet fear to disturb river and lake.” The artistic conception is fresh, moving, romantic, and imbued with “Zen.” It was written just before the end of the Sino-Japanese war, and the painting has two more inscriptions that state Zhang’s mind: “Two capitals not yet recovered; in Kunming, the joy of boating at Xuanwu Lake, can only be recovered in dreams. I felt a far off cold breeze in scorching summer. June of 1945 at Zhaojue Temple for summer retreat. In tribute to Big Di. Zhang Daqian.”

The second verse is written in an exhilarated tone after he heard of the Japanese surrender: “Sudden news of victory excites wild exhilaration in Patriot Du (referring to a Tang dynasty poet). Jeer at the robbers in wolf skins. Now in front of Shinobazu Pond (Shinobazu Pond, known for its abundance of lotuses, is in Tokyo where Zhang had once stayed and frequently admired flowers while boating), people wash off rouge and take off clothes and jade. Early July, Japan surrendered. The capitals are soon to be returned. With joy, Zhang Daqian.” These two inscriptions forcibly convey his two different moods; the former sentimental while the latter shifts to cheerful; both very real and touching.

The “Big Di” mentioned in the verses refers to Shi Tao (1642-1707), a painter of the early Qing dynasty who influenced Zhang significantly and whom Zhang most revered. When painting lotuses, Shi Tao employed heavy ink to outline the petal tips after painting the flower petals with light ink, making the lotus look more lively and spirited. Also, his technique of outlining plants created fresh, brisk, and exquisite beauty. Zhang inherited the above-mentioned stylistic traits and took their application a step further with his brightly-colored lotuses.

III. Zhang Daqian’s Lotus on Ink Scroll

The other important lotus painting from the National Museum of History is the “Gentle Fragrance at Water Hall,” painted in Brazil in 1962. At the time, Zhang had already fathered a new era in Chinese painting with his splash-ink style, and this scroll can be seen as another pinnacle in his artistic career. Though he created numerous exemplary lotus paintings, very few were executed on scrolls, which pose particular difficulty maintaining cohesion when painting flowers. Also, the narrow, elongated shape of scrolls adds to the difficulty in composition. Therefore, traditionally floral scrolls are often presented in segments, for example as “flowers of four seasons,” with one segment of daffodils; one of chrysanthemum; one of summer lotuses; and one of winter plums. These paintings are often delightful but lack force and tension. However, Zhang’s “Gentle Fragrance at Water Hall” is different. Though measuring 45.5 cm wide and 684 cm long—much smaller than the above-mentioned “Lotus on Large Screen,”—the painting is no less scintillating; it displays compelling magnificence and brushwork of mind-boggling dexterity. It is a true masterpiece of contemporary art, and a chef d'oeuvre among Zhang’s lotus paintings.

Scroll paintings are a uniquely Chinese form; able to connect time, space, and perspectives from different angles in a single visual space. Not only does this make clear that Chinese observe nature through a different worldview than do peoples of the Western world, but also reflects a particular continuity of time. The artist exploits this characteristic of the scroll and releases the vigor and life of the lotus from every angle and every position. Zhang employs constant dashing strokes, fast as the thundering winds gathering clouds, powerful as the momentum of a raging river. An elastic energy can be seen in every stroke. There is a tension between the stems and leaves that gives the painting a rich dynamism. A rhythmic beauty can be found in the rising and falling pattern of the flowers and leaves; in places close-knit, in places free and unrestrained. Nowhere does one find monotony or repetition.

When painting flowers, Zhang especially emphasized the importance of physical observation, a concept deriving from the Ge-wu-zhi-zhi1 theory passed down from the Song dynasty. As a result, although this scroll was completed with loose, freehand strokes, it is strongly realistic; an absolute representation of the lotus. The skilled use of ink of varying degrees of dilution and saturation gives sharp contrast between light and shade.

The verse inscribed on the painting elegantly reads: “Fragrance of Handan (meaning lotus) wafts ten miles, without swell or wave, only ripples; nightfall will surely bring couples to roost, would that there be no west wind blowing.” The poem is concise and polished, depicting a summer night when the fragrant air and shadowy moonlight are evocative of romance.

Another important characteristic of this painting is an abstract and minimalistic quality very much in sync with contemporary art. If we take a close look at the picture, we can discover all the geometric elements of Western abstract painting. This demonstrates the painter’s powerful creative control, and his ability to transcend the boundaries of space and time.

Note1: Ge-wu-zhi-zhi: the study of the nature of things; to gain wisdom by observing natural phenomena.

The artistic maturity and level of excellence seen in “Water Hall Fragrance” goes far beyond that of “Lotus on Colossal Screen,” but only in terms of artistic ambience. After nearly 20 years had passed, it goes without saying that Zhang’s mastery of art had experienced tremendous advancement. As majestic and well-composed as the “Lotus on Colossal Screen” is, it pales in comparison with “Water Hall Fragrance,” on account of its unruly dynamism. Hindered by its great size, Zhang had to complete the immense painting portion by portion and layer by layer. Ultimately, it is always easier to deploy one’s skills on a smaller canvas.

The lotus has an innate grace and purity, and carries a certain cultural symbolism. For example, the Buddhist Bodhisattva is often seen holding a lotus flower. The Song-dynasty theorist Zhou Dunyi also admired the lotus as a beauty that, alone among a hundred lesser peers, could emerge immaculate from the muddy earth. Appreciation of Penjing (ancient Chinese art of growing plants, akin to Bonsai) was one of Zhang Daqian’s favourite leisure activities. He confessed that among all the flowers, he found the plum blossom to be the most endearing. He even called himself a “Plum Addict.” Although he produced many paintings and poems on the theme of the plum blossom throughout his life, in terms of quality and quantity, they never attained the heights he reached in lotus painting. Therefore, to call him a “Lotus Addict” would seem quite a bit more appropriate.

Zhang Daqian loved the lotus and composed many poems in its honor. His language is natural and fresh, and sometimes sparkles with ingenuity. It is a pity that his writings are so overshadowed by his paintings and hence rarely known.

He once wrote a poem for his piece, “Rain Lotus”: “Dewy waves and far into the night, cool skin yet still reminiscent of summer; empty water hall and cold moon, hand fanning with green sleeves.” Another poem for the white lotus goes “Bright moon once called the white-jade dish, its brimming passion shines over the jade railings; the west wind spreads fragrance all the night, clad in silk cloth and surprised by the slight chill by the pond.” Both poems evoke an ethereal atmosphere; a romantic and fantastical purity. Observe the aesthetics of the painting while reading the poems and one will discover a deeper level of sophistication. The unity of poetry, calligraphy, and painting embodies a unique aesthetic and spiritual dimension in Chinese culture; a unique vision in the field of visual arts; and a heritage of cultural wisdom for her people. Zhang inherited this tradition and raised the art of lotus painting to a plain never known to his predecessors.

Zhang Daqian was romantic by nature. He observed lotuses, drew lotuses, wrote lotuses—his love was profound. It was this deep fondness that lead to his great achievements in ink lotus painting. He not only incorporated all the strengths of different painting schools, but also opened the way to whole new levels of creativity. Thanks to the National Digital Archives Program, these two ink lotus masterpieces can reach more audiences than ever. This is indeed a most pleasing outcome for every art lover. The “Lotus on Colossal Screen” has been especially chosen as one of the “Fourteen Splendours” to be unveiled complete with a detailed caption and multimedia features. All those interested can go to the website of the National History Museum to view them.

End of December, 2009 at Nanhai Academy, Taipei

National History Museum Digital Archive: Collection of Zhang Daqian’s Lotus Masterpieces

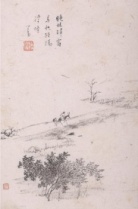

Landscape Painting by Pu Xinyu and Zhang Daqian

Subject and Keywords: support: Cotton Paper

Description: Mounting Style: Album

Data Identifier: serial number: 1992/2338-1/2

Landscape Painting by Pu Xinyu and Zhang Daqian

Subject and Keywords: support: Cotton Paper

Description: Mounting Style: Album

Data Identifier: serial number: 1992/2338-1/2

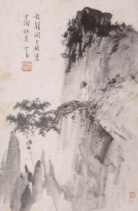

Landscape Painting by Pu Xinyu and Zhang Daqian

Subject and Keywords: support: Cotton Paper

Description: Mounting Style: Album

Data Identifier: serial number: 1992/2338-1/2

Landscape Painting by Pu Xinyu and Zhang Daqian

Subject and Keywords: support: Cotton Paper

Description: Mounting Style: Album

Data Identifier: serial number: 1992/2338-1/2

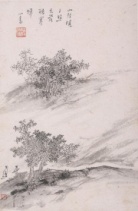

Landscape Painting by Pu Xinyu and Zhang Daqian

Subject and Keywords: support: Cotton Paper

Description: Mounting Style: Album

Data Identifier: serial number: 1992/2338-1/2

Landscape Painting by Pu Xinyu and Zhang Daqian

Subject and Keywords: support: Cotton Paper

Description: Mounting Style: Album

Data Identifier: serial number: 1992/2338-1/2

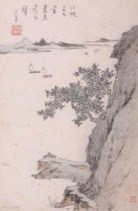

Landscape Painting by Pu Xinyu and Zhang Daqian

Subject and keywords: support: Cotton Paper

Description: Mounting Style: Album

Data Identifier: serial number: 1992/2338-1/2

|