TELDAP Collections

| The Ancient Art of Writing: Selections from the History of Chinese Calligraphy |

|

Introduction To meet the need for recording information and ideas, unique forms of calligraphy (the art of writing) have been part of the Chinese cultural tradition through the ages. Naturally finding applications in daily life, calligraphy still serves as a continuous link between the past and the present. The development of calligraphy, long a subject of interest in Chinese culture, is the theme of this exhibit, which presents to the public selections from the National Palace Museum collection arranged in chronological order for a general overview. The dynasties of the Qin (221-206 BCE) and Han (206 BCE-220 CE) represent a crucial era in the history of Chinese calligraphy. On the one hand, diverse forms of brushed and engraved "ancient writing" and "large seal" scripts were unified into a standard type known as "small seal." On the other hand, the process of abbreviating and adapting seal script to form a new one known as "clerical" (emerging previously in the Eastern Zhou dynasty) was finalized, thereby creating a universal script in the Han dynasty. In the trend towards abbreviation and brevity in writing, clerical script continued to evolve and eventually led to the formation of "cursive," "running," and "standard" script. Since changes in writing did not take place overnight, several transitional styles and mixed scripts appeared in the chaotic post-Han period, but these transformations eventually led to established forms for brush strokes and characters. The dynasties of the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) represent another important period in Chinese calligraphy. Unification of the country brought calligraphic styles of the north and south together as brushwork methods became increasingly complete. Starting from this time, standard script would become the universal form through the ages. In the Song dynasty (960-1279), the tradition of engraving modelbook copies became a popular way to preserve the works of ancient masters. Song scholar-artists, however, were not satisfied with just following tradition, for they considered calligraphy also as a means of creative and personal expression. Revivalist calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), in turning to and advocating revivalism, further developed the classical traditions of the Jin and Tang dynasties. At the same time, notions of artistic freedom and liberation from rules in calligraphy also gained momentum, becoming a leading trend in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Among the diverse manners of this period, the elegant freedom of semi-cursive script contrasts dramatically with more conservative manners. Thus, calligraphers with their own styles formed individual paths that were not overshadowed by the mainstream of the time. Starting in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), scholars increasingly turned to inspiration from the rich resource of ancient works inscribed with seal and clerical script. Influenced by an atmosphere of closely studying these antiquities, Qing scholars became familiar with steles and helped create a trend in calligraphy that complemented the Modelbook school. Thus, the Stele school formed yet another link between past and present in its approach to tradition, in which seal and clerical script became sources of innovation in Chinese calligraphy.

Selections

"Oracle script" refers to brushed or engraved writing on turtle shells and animal bones that were excavated mostly at the late Shang dynasty capital of Yinxu (modern Xiaotun, Anyang, Henan), and it is also found at recent excavations of Zhou dynasty sites. Most contents deal with divinations, including sacrificial offerings and hunts. The form, pronunciation, and meaning of oracle script characters had already reached a mature stage of development. Tung Tso-pin was a renowned scholar in the humanities who took part in eight excavations at the ruins of Yin, making important contributions to the study of oracle script. This poem on "The Beauty of Jiangnan" done in oracle script features elegant yet dignified brushwork that has much of the harmony of these divination texts.

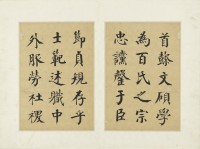

Yang Xian (style names Jichou, Jianshan; sobriquets Yongzhai, Miaosou) was a native of Gui'an in Zhejiang (modern Huzhou). From a Prefectural Graduate's family, he was a staff member for Zeng Guofan and Li Hongzhang, becoming Prefect of Changzhou and Songjiang. He was famous in the late Qing dynasty for studying clerical script, "not leaving out anything from Han steles." He devoted much of his time to copying steles, achieving a name for himself. Most works he copied were steles in clerical script, influencing late Qing calligraphy circles and even Japan. In this copy from the King Luxiao engraving of the Western Han, the brushwork is sprightly and fluid, yet the rise and fall of the brush is pleasantly resilient, revealing a mature yet unusual touch.

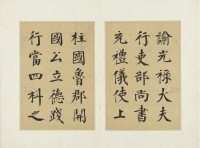

Calligraphing Yan Zhenqing's Self-written Announcement of Appointment Qian Feng (style names Dongzhu, Yuefu; sobriquet Nanyuan) was a native of Kunming, Yunnan. A Presented Scholar of 1771, he served as Deputy Officer of Transmission and Imperial Censor. At the time Heshen was in power, but Qian still censured him and succeeded in impeaching such officials as Bi Yuan, Governor General of Shaanxi-Gansu, and Guotai, Commissioner of Shandong, for corruption. He earned the great respect of people for "defying power and clearing away obsequiousness." In his life, Qian Feng admired the person and calligraphy of Yan Zhenqing. This work has strict and proper characters, the power solemn without a stroke missing, much in the spirit of Yan Zhenqing. This work was donated by Messrs. Tann Boyu and Tann Jifu.

This work is a tracing copy of Wang Xizhi's "Changfeng," "Xianshi," and "Sizhi feibai" calligraphy in cursive script using the method of "double outlines filled with ink." Also found in "Modelbooks of the Chunhua Pavilion," this work is notably different in terms of style, so it was probably not copied from that source. Though attributed as a copy by Chu Suiliang, throughout it bears the structure and manner of Mi Fu's calligraphy. The brush habits and lines being quite similar, it suggests this is probably a Song dynasty outline copy of Mi Fu's freehand interpretation. The ink tones throughout are mellow and rich, the stops and starts of the strokes along with the turning points clearly revealing traces of the brush, demonstrating the precision of this tracing copy.

Hongli, known by his temple name Gaozong and more often by his reign name Qianlong, was on the throne for 60 years. Highly knowledgeable in Chinese culture, he was also a gifted writer and enjoyed composing prose and poetry. He was a capable painter and especially practiced calligraphy. His poetry and calligraphy, also appearing in engravings, are particularly numerous. This folding fan originally was a letter written by Su Shi to his friend Chen Jichang with New Year greetings. It was engraved and also appears in "Calligraphy of the Kuaixue Hall" and "Calligraphy of the Sanxi Hall," the original now in the Beijing Palace Museum. Though a copy, it reveals Qianlong's precision in brushwork with his full and beautiful calligraphy.

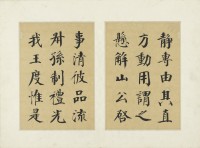

Chu Deyi, a native of Yuhang in Zhejiang, changed his name to avoid a taboo character in the Xuantong Emperor's name. He also had the style names Songchuang and Shouyu. In calligraphy, he was good at clerical script and especially admired the Ritual Vessels Stele, taking a sobriquet to reflect it. With an interest in antiquities throughout his life, he focused on studying bronze and stele inscriptions, also specializing in seal carving and calligraphy. Among modern Bronze and Stele scholars, he also was a seal carver and calligrapher. This work is a compilation from different renowned calligraphic sources ("Mushi fu dun," "Han Kong Qian jie," "Tang Sun Guoting Shupu," and "Tang Ouyang Xun Liquan ming"), combining bronze, clerical, cursive, and regular scripts all on one fan. The marvelous variety makes for considerable appreciation.

Text and images are provided by National Palace Museum

|