TELDAP Collections

| The Development of Calligraphy and Painting Exchanges between Taiwan and Japan During the Japanese Colonial Period |

|

This article is provided by the Taiwan Digital Archives Request-for-Proposals Project, the subsidiary project of Taiwan Digital Archives Expansion Project For thousands of years, human histories and cultures have been recorded in the form of written texts in different parts of the world. Writing tools have evolved over the ages from small twigs, carving knifes, hair brushes, fountain pens to computer keyboards. Various materials used for writing range from early stone and clay tablets through paper to modern electronic books. Different tools and materials people employ for writing are indicative of different social and cultural traits developed in different times. In China, writing has been practiced for more than three thousand years with Chinese writing brushes and, perhaps more than anywhere else, came to be recognized as an important type of documentary tool.

Calligraphy and painting nowadays serve mostly as vehicles for expression, but before they were an indispensable part of life, especially for the Chinese men of letters in earlier times. The starting point for the evolution of calligraphy and painting styles in Taiwan, on closer examination, can be traced back to the time when the Ming supporter, Cheng Chengkung (Zheng Chenggong, also known as Koxinga) retreated to the island and ushered in a renaissance of ancient Chinese culture. Moreover, during the Qing dynasty the mainland literati and imperial examination graduates who migrated to Taiwan made great contributions to the development of Chinese calligraphy and painting. Therefore, at that time Chinese artistic traditions remained very much alive in Taiwan. When Japanese took over the island in 1895, Taiwanese came into contact with the Western conception of learning. New political forms and new patterns of thought spread all over the island and gradually transformed the ways people learned and expressed themselves. During the fifty years of Japanese rule, this modernist trend in learning also exerted influence on Taiwan’s calligraphy and painting, which began to turn away from the standards that had characterized ancient Chinese art.

Though the Japanese consolidated their colonial rule by coercively promoting Japanese culture and modern education in Taiwan, they set great store in traditional humanistic Chinese philosophy. What they admired most about Chinese culture was the legacy of calligraphy, one of the literary pursuits that dominated the leisure time of the men of letters. Japanese calligraphic educators in Taiwan include Kyouzan Yamamoto (1863-1934), the talented disciple of the calligraphy master Meikaku Kusakabe and a commissioner for Taiwan Governor-General's Office, the traveling calligraphers Kaikaku Niwa (1863-1931) and Hidai Tenrai (1872-1939), and the calligraphy instructor Konan Nishikawa (1878-1941). These influential figures in Chinese calligraphy, through various channels of promotion such as exhibitions of calligraphy and painting works, calligraphy albums and magazines, gradually revolutionized Taiwanese artists’ learning approaches to calligraphy and painting.

In terms of cultural fusion, one particular aspect of Japanese culture involves a grasp of the basic Chinese language. Most of the Japanese scholar-officials who came to Taiwan had already acquired a cultivated knowledge of Chinese poetry and prose; thus, despite language differences, they were able to chant Chinese poems and form friendships with Taiwan’s educated elites in the literati salons. Both calligraphy and painting became the most popular platforms on which to facilitate such intellectual communication.

Yet for all the political irreconcilabilities and emotional crosscurrents pervasive during the Japanese colonial period, can we still perceive the cultural exchanges inherent in the Taiwanese and Japanese contemporaries’ works of poetry, calligraphy and painting?

The Calligraphy and Painting Exchanges between Taiwan and Japan

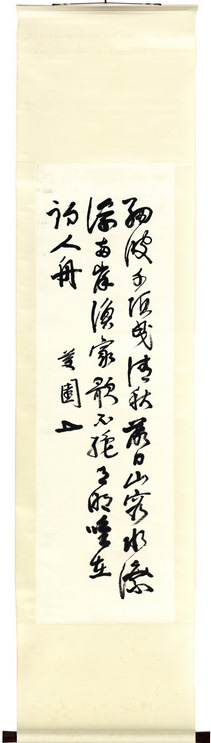

A thousand acres of waves throw up the autumn glow;

Rippling water reflects the mountain against the sunset.

On either bank the fishermen’s songs sound endlessly;

The bright moon lies fair only on the poet’s ferry. (Figure 1)

The above poem was composed by Kodama Gentar?, the fourth Governor-General of Taiwan. As a military commander of distinction who enjoyed poetry, Kodama Gentar? resorted to promoting literature and culture in an effort to unify Taiwan under Japanese control. In 1899 he invited a number of Taiwanese poets to chant poetry and paint at his private villa called “South Vegetable Garden” located in Guting district of Taipei. Later he hosted “The Grand Assembly for Promoting Literature”, a literary gathering for the island’s poets which achieved unprecedented success in prompting a flourishing Taiwan’s poetry society.

Under Kodama Gentar?’s administration, Got? Shinpei, the head of civilian affairs inTaiwan, contributed considerably to the modernization of Taiwan. Apart from his administrative strengths, he distinguished himself through his love of writing and for his numerous Chinese works. Presented below is one example of his poems:

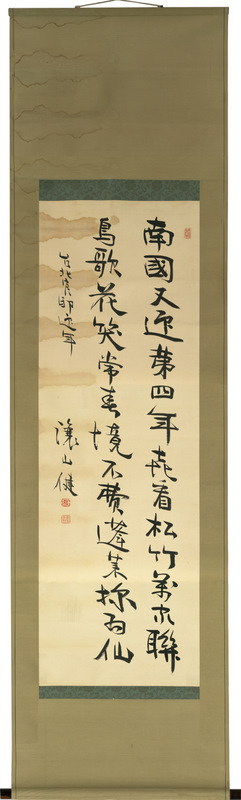

Far above the clouds towers Jade Mountain;

Mists obscure the source of the Zhuoshui River.

For a thousand miles a thicket green is unfurled to the south-west;

How many mountain ridges rear like flights of steps?

Signed Shinpei on an official visit to Jiayi (Figure 2), this work describes the view Got? Shinpei observed when he visited Jiayi and Tainan regions. As a scholar- bureaucrat, he recorded the landscape of Taiwan in his poems and essays, which are all remarkable pieces bearing high historical and artistic value.

Figure 1: Seven-character poem in running-cursive script (vertical scroll), produced by Kodama Gentar?.

(Source: National Tsing Hua University)

Figure 2: Seven-character poem in running-cursive script (large size vertical scroll no.3), produced by Got? Shinpei.

(Source: National Tsing Hua University)

During the Japanese colonial period, one hundred scenic spots were taken from Taiwan’s landscape attractions and labeled as “One Hundred Great Scenic Spots in Taiwan” or “Historic-Cultural Sites”. This measure the Japanese took to assert their control on Taiwan also showed their great appreciation for the beauty of the island. Den Kenjir?,1 the eighth Governor-General of Taiwan, wrote the following poem while staying in Taipei:

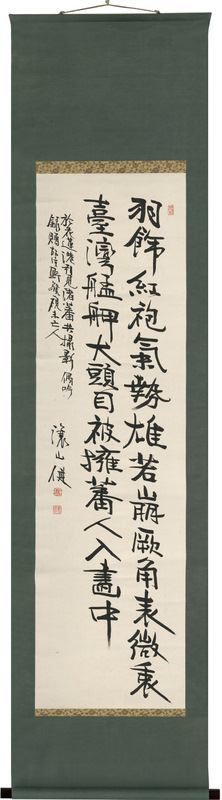

Residing in the south country for the fourth year in a row,

I have loved pines and bamboos surrounding ten thousand homes.

Long spring days, on the island, flowers in full bloom—

There I felt like an immortal retiring in Penglai. (Figure 3)

This poem, describing Den Kenjir?’s four-year residence in Taiwan, vibrates with intense joy felt by an overseas governor, who could not help but visualize himself wandering off onto a celestial island called Penglai. One of Den Kenjir?’s primary concerns was to ensure equal treatment to both Japanese and Taiwanese people. In 1920 he received several Takasagozoku tribesmen (Formosan indigenous peoples) in Hualien Harbor; after that, he composed a poem to commemorate the scene in which they were photographed together:

The masculine figures clad in red costumes, their plume headpieces,

Like animal horns, shaking violently in their attentive salute.

There side by side in the photograph were found

The chief of Banka and the invited tribesmen. (Figure 4)

This work reflects the relationship between a Japanese governor and Taiwan’s indigenous peoles at the time. On the right-hand side of the poem are inscribed characters Tianyuan quwei, which means “Pastoral Pleasure”.

Figure 3: Calligraphy in regular script (vertical scroll), produced by Den Kenjir?.

(Source: National Tsing Hua University)

Figure 4: Calligraphic inscription, produced by Den Kenjir? during his official tour in Hualien, Taiwan

(Source: National Tsing Hua University)

After the abolition of the long-run imperial examination system, Taiwan’s Confucian scholars lost the means by which to advance themselves to school instructors or civil service positions. Therefore, only through attending poetry society events and literary salons could they have chances to demonstrate their classical knowledge and literary talents.

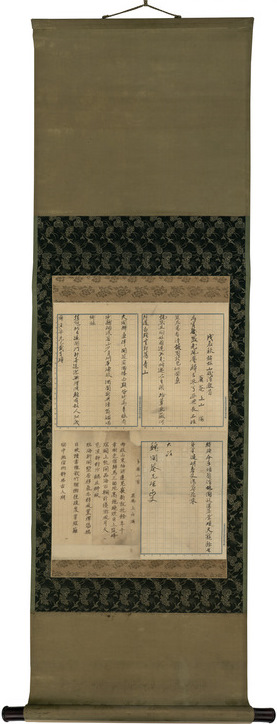

By interacting with Japanese scholars at salon gatherings, Taiwan’s men of letters sought to establish their social connections with bureaucrats; Japanese governor-generals in return treated Taiwanese patronizingly by manifesting their literary sophistication and their respect for a Confucian system of government. For example, figure 5 shows the very poems chanted by the eleventh governor-general Kamiyama Mannoshin and the Hsinchu-based scholar Wei Qingde2. Kamiyama Mannoshin was appointed Governor-General of Taiwan in 1926 and held the position for almost two years. During his tenure he set up the Culture and Education Bureau. He was also the founder of the Taipei Imperial University (today’s National Taiwan University), who recruited Taira Shidehara to serve as its first principal and arranged for the establishment of two academic faculties—the Culture and Education Faculty and the Science and Agriculture Faculty. The Culture and Education Faculty provided a course in the History of the Southern Ocean, organized lectures on folk ethnology, and launched Taiwan-related researches, which yielded a trove of important documentary data.

In 1927, Taiwan Governor-General Office, under the assistance of the Japanese artists T?ho Shiotsuki, Gobala Kodoo and Kinichiro Ishikawa, founded the “Taiwan Fine Art Exhibition” in order to institutionalize a new art movement that was well under way. At that time Taiwan’s artists began to experiment with new Western and Japanese techniques used in painting; for them an ink landscape painting, aside from the scene itself, should capture the sensations that a scene evokes in the artist’s very being. The misty view of Tamsui, one of the favorite painting themes among contemporary painters, gave the landscape an ethereal aura that particularly appealed to the Nanga School (also known as the Southern Painting School). T?ho Shiotsuki, the first painter who introduced to Taiwan the materials and techniques for oil painting, once remarked, “No other place in Japan can compare with Taiwan concerning its multicolored, ever-changing scenery.”

Japan’s modernist movement, which brought forward new interpretations for the term “landscape”, revolutionized the artist’s visual perception of nature and turned a new page in the evolution of mountain painting. Kinichiro Ishikawa recounted his positive impression of Taiwan: “A landscape characterized by bold and vigorous outlines of mountain peaks and rich natural color palettes”. Particularly interested in Taiwan’s alpine plants, the watercolor artist Banka Maruyama3 (Figure 7) created paintings, which showcase a typical image of Taiwan, that consisted of high mountains, water buffalos and camphor trees. In addition, based on his traveling experience in Taiwan, Banka Maruyama offered his own definition of “landscape” and divided Taiwan’s landscapes into 3 categories: body and color, majestic beauty and elegant beauty, scenic views and historical views.

Figure 5: Poems in running script (vertical scroll), produced by Kamiyama Mannoshin and Wei Qingde

(Source: National Tsing Hua University)

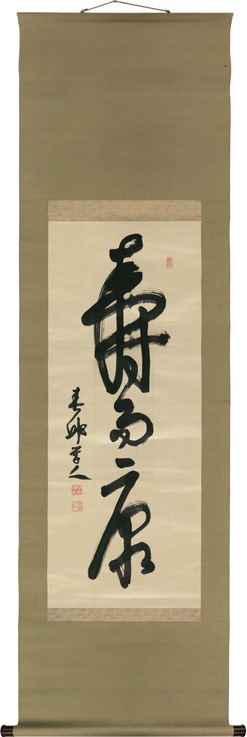

Figure 6: Long Life and Great Health, inscribed by Taira Shidehara (also known as the Green Hill Scholar)

(Source: National Tsing Hua University)

Figure 7: Short album of calligraphy in running-cursive script (Aquatic Life in Taiwan), produced by Banka Maruyama

(Source: National Tsing Hua University)

The selected works as shown in the figures, significant both artistically and historically, are part of the collection made by Yang Rubin and Fang Shengping, professors of the Department of Chinese Literature at National Tsing Hua University. Clear images of these calligraphy and painting pieces are archived and now available on the website named “Digital Archiving of Taiwan’s Calligraphy, Painting and Historical Document, Late 18th Century— mid 20th Century,” which is presided over by several faculty members of National Tsing Hua University—Hsieh Hsiaochin and Ma Mengching, professors of Center for General Education, Liu Shuqin, professor of the Institute of Taiwan Literature, and Chuang Hweilin, director of the National Tsing Hua University Library.

This collection, totaling 407 items, comprises not only a great number of artifacts dated a hundred years ago but also two-thirds of the governor-generals’ works during Japan’s fifty-year colonial period. Such a massive and well-ordered collection is a rare gem in Taiwan. From a cultural perspective, these collected calligraphic and painting works reveal the frequent interactions among the Taiwanese and Japanese contemporaries. Particularly after the Meiji Restoration, Japan saw an ever-increasing number of overseas official visits, personal travels and informal tours of historic sites in Taiwan. Through such contacts Chinese poetry and calligraphy became the dominant means of communication for Taiwanese and Japanese intellectuals. Also, the vast collection of the Chinese works in prose and verse composed by the Japanese to record their thoughts on Taiwan not only shows much cultural and artistic merit but also serves as a reference point in the analysis of the cultural exchanges made during Japanese occupation.

Notes:

1. Den Kenjir? (1855-1930), born in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, received his early education in Chinese studies. After the takeover of Taiwan, he was immediately appointed Minister of Communications for the Bureau of Taiwan Affairs founded by Japan’s cabinet, so he had been involved with Taiwan’s affairs for a long time. From October 1919 to September 1923, Kenjir? assumed the position as the first civilian Governor-General of Taiwan. During his tenure, in keeping with the guiding principles governing overseas expansion, a new policy where Taiwan was viewed as a territorial extension of mainland Japan was executed, thus marking the beginning of a colonial government aimed at the assimilation of Taiwanese into the Japanese society.

2. Wei Qingde (1886-1964), also known by his style name Runan, was a native of Hsinchu, Taiwan. His father was a Chinese language teacher, whose private instruction made him well versed in poetry and prose at a young age. In 1910, he became one of the first members involved in the founding of the Ying Poetry Society, and succeeded Xie Xueyu as its third president. As a well-known poet in Taipei, Wei was later promoted to both journalist and Chinese division director for Taiwan Daily News under the earnest recommendation from Hotsuma Ozaki, both a Japanese Sinologist and the chief editor of Taiwan Daily News.

3. Maruyama Banka (1867-1942), originally named Kensaku, was a western art painter born in Nagano Prefecture, Japan. He received his first formal training in 1883 from the literati painter Katei Kodama, and then went to Tokyo to study western painting. In 1907 he and his artist friend Oshita Tojiro founded the “Japan Institute of Watercolor Painting”; since then Maruyama Banka had become an active watercolor painter widely recognized in art circles. From 1931 to 1934, he held several exhibitions of his watercolor sketches in Taiwan.

|