TELDAP Collections

| Marriage in Traditional Taiwanese Han Society |

|

In the early years of Qing rule, a disproportionately male population in Taiwan led to the prioritization of finances in affairs of marriage. To marry, the groom had to prepare a huge amount of betrothal money, while the bride had to be accompanied by a hefty dowry, causing marriage to become a ritual show of wealth.

Although as time went by the western plains of Taiwan became more and more developed and populated, in patriarchal, agriculturalist Han society, inheritance remained a male-dominated system from which females were excluded. The concept in Han society that “unmarried women must obey their fathers, married women their husbands, and widowed women their sons,” was strictly binding. Therefore, a woman was required to marry in order to secure her place in this life as well as in the next; to secure a place for her name in her husband’s genealogy and on his shenzhu pai (spirit tablet); and for her ancestors to make sacrifices to her after her death. Moreover, in order to win the right to inheritance and gain power in the family she married into, she had to prove her ability to produce offspring that would continue the family lineage.

Therefore, single women were not much valued in a family and could only become a member of society through marriage. In addition, since a dowry was a huge financial burden for a family, it was not unusual for family members to treat women as merchandise. They were sold or used as collateral to relieve the family of financial strain when difficulties struck, or even in other circumstances, such as when the woman’s Bazi (method of Chinese fortune telling based on time and date of birth) was judged to be unlucky, etc.

Women at this time could not refuse to marry, nor could they choose who to marry. A woman’s destiny in adulthood hung on the husband chosen by her parents or matchmaker. There is nothing that illustrates these women’s situation better than the old saying that goes, “Woman’s fate is that of a seed (i.e. not her own); marriage to a good husband shall bring a life of fortune and comfort; marriage to a bad husband shall bring a life of endless toil and worry.”

A 1912 wedding photo of Lin Zushou (groom) from Banqiao and Cai Jiaoxia (bride) from Qingshui.

(Source: Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica)

Due to the emphasis placed upon money in marriage, many poor young men and women were at a disadvantage in their search for a life partner. Because the society was rigidly patrilineal, many alternative types of marriage were invented to make sure that male heirs were produced to ensure continuity of the family name. These alternatives included matrilocal marriage, shim-pua marriage, concubinary, and so on, and were generally referred to as xiaoqu (small marriage).

Generally speaking, families lacking a male heir could adopt a boy from another family in the clan or outside of the clan to ensure the continuing of the family’s name. Alternatively, they could ‘recruit a son-in-law’, or zhao xu, for a household daughter. When a son-in-law was ‘recruited’, he would move into his wife’s house, take responsibility of the wife’s family affairs, and was expected to produced heirs for the wife’s family. Widowed women might also ‘recruit a husband’, or zhao fu, to provide financial security for a household with young children and older parents in need of support, or to produce heirs in cases where the husband died before one was born. Through the practice of zhao fu, the household name could be passed on.

Some families chose, rather, to raise a young girl adopted from another family as a future daughter-in-law. This practice, called yangxi, could save the family a fortune in wedding-related expenses, since the adopted girl could be wedded to a household son after reaching marriageable age without any unnecessary extravagance. Moreover, as the daughter-in-law had been raised by the husband’s parents, she would not need to adapt to the new environment as normal brides would.

These alternative types of marriage were usually arranged with specific goals in mind. Therefore, they were often accompanied by a written contract, on which the rights and responsibilities of the signing parties were stipulated in order to avoid future disputes. Several important issues were typically dealt with in this kind of contract.

First was responsibility for worshipping the ancestors of the bride’s family (or the family of the widow’s late husband). Second, the surnames of the children produced by the marriage would be established. The contracting families would negotiate which family’s surname the first and second child would assume, and if there were more children produced, which surname these children would take. The decisions were usually made based on the contracting families’ respective influence and bargaining power. Finally, conditions relating to inheritance of the bride’s family’s wealth, the upkeep of the ancestral shrine, support and funeral arrangements for older members of the bride’s extended family, and so on were also commonly found in these contracts.

No matter what type of marriage was proposed, a woman in traditional Han society had no say in matters regarding her marriage. Her destiny was governed and dictated by the social and cultural values that were reflected in these matrimonial traditions. As times have changed, the shackles of marriage are no longer an unbreakable constraint on modern women. In the future, we may see even more alternative forms of marriage come into place. One hopes, however, that no matter which type of marriages bind people together, they are setting out on the road to true happiness.

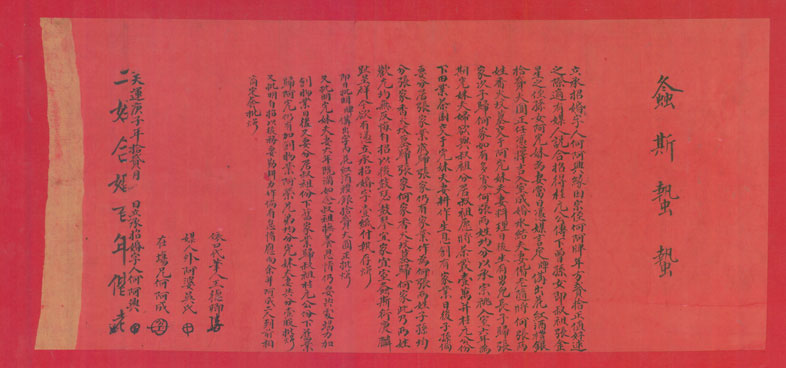

Marriage contract drafted by He A’xing in 1901

(Source: Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica)

A contract can be any kind of record documenting an agreement made between different parties in a society. A contract for marriage or purchase or sale of individuals was usually drafted on a red paper or cloth. The goal was to establish written terms and conditions concerning the rights and responsibilities of the signing parties.

This marriage contract was written in December, 1901, by He A’xing for the marriage between his nephew, He A’pai, and the grandniece of Zhang Jinxing, Zhang A’wan. The terms and conditions of this contract are as follows: Under the arrangement of the uncle of the groom, He A’xing, He A’pai will marry Zhang A’wan and enter the Zhang household. The newlyweds will live in the Zhang house for six years. The newlyweds will be responsible for continuing the family line and the upkeep of the ancestral graves of both families. The first son born will be surnamed Zhang and the second son, He. As for the rest of the children, half will be surnamed Zhang and the other half He. When the six-year period is over, the couple can choose to move out of the Zhang household and will be apportioned farm lands and tea plantations so that they may make a living. Afterward, if children born to them wish to leave the family home, the family inheritance will be passed down to children surnamed Zhang. Only in the case where there is surplus inheritance will wealth be distributed evenly between all the children. If the couple lives in the Zhang house beyond the six year period, the inheritance will be apportioned differently.

Auspicious words and phrases were commonly used on a marriage contract. In this particular contract, the words ‘螽斯蟄蟄’ (zhongsi zhizhi) are a reference to a classical poem entitled ‘Zhongsi’ (螽斯, translated variously as Grasshopper, Locust, etc.) from the Book of Songs (section: Airs of the States (Guo Feng), chapter: Odes of Zhou & South), to symbolize a marriage blessed with many children.

|