|

The Archives of the Institute of Taiwan History (ITH) at Academia Sinica holds a wide variety of historical sources pertaining to women of Taiwan; these materials date back to the Qing dynasty and can be examined from three aspects— “Traditional Women,” “Transition of Fate,” and “Self Expression.” They illustrate how Taiwanese women emerged from traditional family to modern job market and social activities with activism and independence.

The collections of marriage documents, contracts, photographs, diaries, and personal documents presented here are selected from the digital archives of the ITH. With the help of advanced digital technology, not only can we preserve the diversity of Taiwan’s historical archives, but this also allows us to witness the change in women’s status from dependency to autonomy during the past century in Taiwan.

Traditional Women

The conventional idea that a woman should “obey her father before marriage, her husband during married life, and her sons in widowhood” reveals how Taiwanese women’s existence was dependent on men in the traditional society. Unlike the male heirs who bear the duty of carrying on the family line, unmarried women were often sold as commodities and became others’ adopted daughters, child brides, indentured servants, or even prostitutes during economic hardships.

| |

A wedding photo of Lin Zushou and Cai Jiaoxia, April 27, 1912.

The four young girls and the two women standing beside the newlywed couple were the accompanying maids who would take care of the bride's daily life in the future.

|

Even after becoming wives, Taiwanese women still had no personal autonomy. Even in instances where the husband died, leaving the women behind, his family’s elders would sometimes choose to adopt another man into the family to serve as the widow’s new husband, who would accept the responsibility of raising the children or carrying on the family line.

|

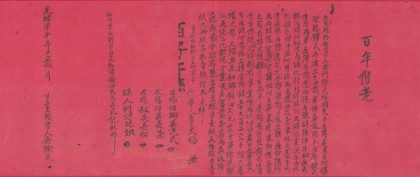

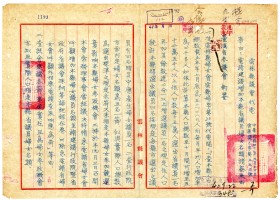

An uxorilocal marriage agreement by Mrs. Wu (née Xu), 1881.

When Mrs. Wu’s eldest son passed away, he left behind his wife (née Zhong) and two sons. In order to raise the family, Mrs. Wu adopted a son-in-law, Zhang Agou, to serve as the widow’s new husband.

|

In traditional marriage life, husbands were highly respected by their wives. Only when there were no male elders in the family did the adult females preside over the household. For example, Chen Ling (1875-1939, wife of Lin Jitang of Wufeng) became the head of household after her husband died. Her diary recorded the affairs such as the management of servants, land sales, farmland rentals, and ancestral worship. In some cases, adult women with no patriarch in the family could not only deal with family property matters but also attend the contract signing processes.

|

|

|

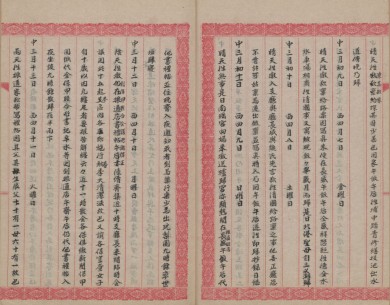

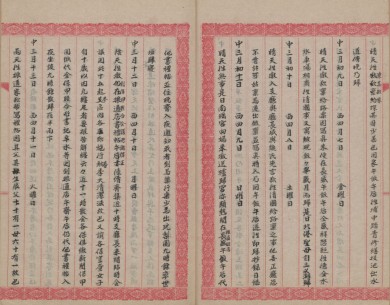

The document on the left is an allotment agreement held by A-Zhao and her younger brother, Wu-Sheng, in 1794. The document on the right is such an agreement as made by Mrs. Li (née Lin) in 1875.

The plain aborigines (Pinpu tribe) woman A-Zhao could share family property and held the same position with men. In contrast, the traditional Han women like Mrs. Li could not inherit family property. Only when there were no male elders could women preside over the family distribution at the witness of the relatives.

|

The Transition of Fate

The lives of women in traditional society, whether rich or poor, were centered around the family. Those from the gentry families were especially secluded in their residence due to the immobility caused by footbinding.

(Courtesy to the

Pingdong Hsiao Family

Ancestral Hall) |

|

|

| Photo 1 |

Photo 2 |

Photo 3 |

|

Photos 1 and 2, taken during the Japanese colonial period, portray women of the Hakka ethnicity in Pingdong and a pair of indigenous women from the Wushe area, respectively. Photo 3, from the same era, is entitled “Women from the Min clan with feet bound.”

Compared to the natural feet of the Hakka and indigenous women, the feet of women from traditional Han families were bound by mothers at the age of four or five; this practice was especially prevalent in families originating from the southern Fujian province of China. The more exquisitely and finely bound a woman’s feet were, the higher the price she would fetch on the marriage market.

|

During the Japanese colonial period, the practice of footbinding was considered as an uncivilized custom. The government implemented a series of policies, ranging from persuasion of the gentry, to the “anti-footbinding movement” through the Baojia system (a community-based law enforcement system, also known in Japanese as the Hoko system) that resulted in a significant reduction of the number of women with bound feet.

|

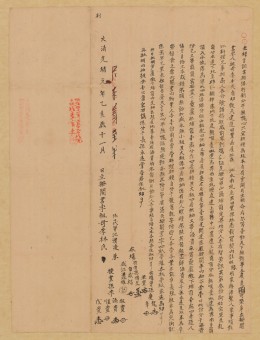

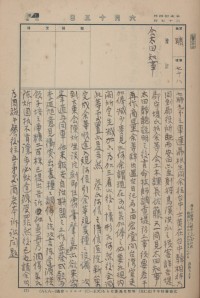

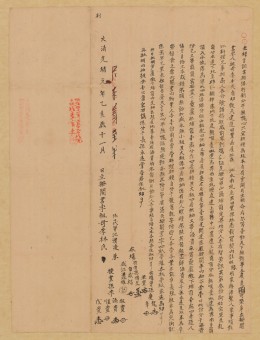

“This Diary of the Shuizhu Villa’s Host (Zhang Lijun),” October 4, 1911.

Zhang Lijun, the baozheng (a communal authority under the Baojia system) of Fengyuan, recorded in his diary that in a Baojia meeting held on April 10, 1911, the branch director ordered all baozhengs “to check all girls under ten years of age within their respective baos (a unit comprised of multiple families) for bound feet; and that those who were found to have bound feet must file a report upon having their feet unbound.” This record illustrates how the Government-General of Taiwan promoted the unbinding policy through the Baojia system.

|

Following their physical emancipation, women walked out of traditional family life and entered new schools to receive education, dismissing the conventional notion that “a virtuous woman is an ignorant woman.”

|

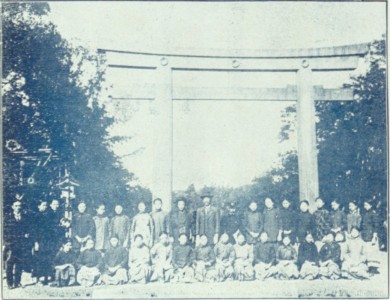

This photo is of thirty Taiwanese female students of the Taihoku Girls High School worshiping at the Meiji Jingu Shrine in Tokyo, in November 1920.

In order to fulfill their goal of colonial control, the Japanese colonial government invited Taiwanese students to come to Japan, enjoy its scenery and visit its historical sites; meanwhile, these female students were essentially taught how to act as Japanese women, in that they were educated in Japanese traditional and popular customs, as well as instructed in Japanese civil and military culture.

|

Women from well-to-do families who were eager for education would even study abroad, mostly in Japan. Except for those who attended missionary schools due to religious reasons, many of them majored in medicine, household management, music, and arts.

|

|

|

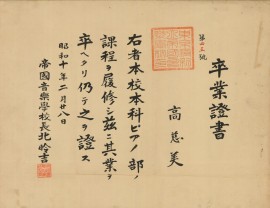

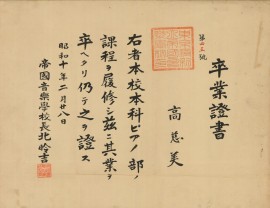

The document on the left is Ms. Gao Cimei’s diploma received from the Tokyo Imperial School of Music in 1935.

Gao Cimei (1914-2004, daughter of Dr. Gao Zaizhu) served as a music professor at the Taiwan Normal University in the postwar period. When she was a fifth grader at the Baiko Women’s College in Japan, she wrote down her feelings and experience in her diary.

|

Self Expression

After being liberated from the footbinding custom of the past, Taiwanese women acquired more knowledge and skills through modern education. Their activities and social roles also began to diversify. More and more women started to embark on different professional careers.

|

|

|

The photo on the left is an entry in “The Dairy of Mr. Guanyuan (Lin Hsing-t’ang),” June 13, 1931; on the right is Ms. Cai Axin (蔡阿信), the first Taiwanese female physician.

Lin Hsing-t’ang recorded in his dairy that he visited the Qingxin hospital, owned by Cai Axin (1899-1990, native of Taipei) the first female doctor in Taiwan. The presence of female physicians helped women express their situation of illness and reduced the possibility of delay in treatment.

|

In addition, both governmental and civilian women’s organizations began to emerge one after another. These new organizations endeavored to impart knowledge and develop skills in response to social movements or national mobilization. Their active attitude in the social affairs set an example for other women.

| |

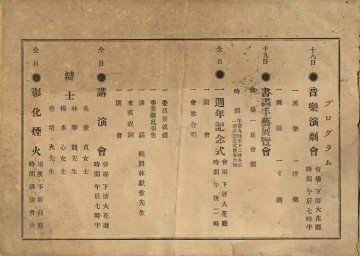

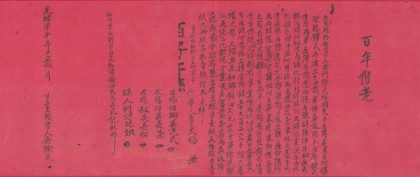

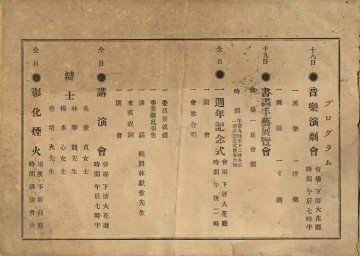

The program for the first anniversary of the Yixin Association, 1933.

The Yixin Association of Wufeng (霧峰一新會) was a social education organization founded in 1932 by the Lin family of Wufeng. The association held a series of activities and speeches from March 18 to 20, 1933. Among the speakers were Yang Shuixin and Wu Suzhen (a.k.a. Wu Tie of Zhanghua, wife of Lin Zibin of Wufeng). Hoping to influence more women, female members in the Yixin Association spread their new ideas through public speeches on woman-related topics such as “Modern Women’s Views,” “Gender Equality,” and “The Practice of Sex Education.”

|

When new Taiwanese women began to participate in social activities, their concerns were not only involved with women and families, but also include the political issues that few women paid attention to before.

|

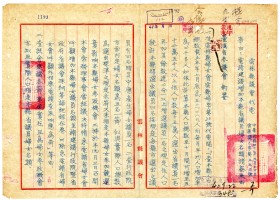

|

This postal telegram, sent by the Yunlin County Council on September 20, 1951, proposed to increase the number of females in the council.

Yunlin County Council applied to the Taiwan Provincial Assembly for approval to increase the number of seats given to women, in an effort to create more opportunities for women to participate in local politics.

|

After World War II, the “Civil Code of the Republic of China” was brought over from the mainland and implemented in Taiwan in 1945. This elevated legal status of women and granted them various rights, such as the ability to take part in the labor force, the right to participate in political and social activities (even to the extend of being directly involved in governmental and political affairs), and the right to vote, all of which enabled women to become their own individuals with a fresh image of independence and a new sense of dignity. Even though women in present-day Taiwan may still be expected to perform many of their traditional family roles, there are those who hope for a society that doesn’t restrict a person based on their gender, in which men and women, out of mutual respect for one another, can together create a new chapter of gender equality in the pages of history.

Text and images are provided by Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica

Exhibition Website:http://herhistory.ith.sinica.edu.tw

|