TELDAP Collections

| Ancient Patterns in the Sea: Ancient Fishing Methods—Stone Fish Weirs |

|

Picture of the Land

When flying to Penghu, many groups of curved lines in the open sea off the coast can be seen from the air. At first glance, what comes to mind are the Nazca Lines in Peru. The lines here are stone fish weirs, a kind of ancient fish trap. Because Penghu has many features advantageous to weir construction, such as wide availability of stones, tidal range and wave action suitable for gathering fish, and so on, the Taiwan Prefecture Gazetteer and Taiwan County Gazetteer contain records regarding stone weirs in Penghu from as early as the reign of Emperor Kangxi, during the Qing Dynasty. According to research by Hong Guoxiong between 1996 and 1999 and Li Mingru in 2005 and 2006, the total number of stone weirs in the Penghu County is 587—the highest concentration in the world.

Fa’xi Weir in Tongliang Village, Baisha Township

(Source / Archival Unit: National Penghu University of Science and Technology Department of Tourism and Leisure)

Living off the Land

Stone fish weirs are the products of ancient wisdom. They are man made fish traps created in response to elements in the natural environment using whatever materials were available. When the tide rises, the sea level is higher than the stone weirs. The fish, attracted by the seaweed within the weirs, will enter the weirs with the seawater. When the tide ebbs, the fish are trapped and unable to escape because the stone weirs are higher than the level of the water.

One of the main materials used to construct weirs is basalt, which is abundant in Penghu.

(Source / Archival Unit: National Museum of Natural Science)

Some stone weirs utilize the habit among fish schools to turn in place upon meeting a curve. At an inward-curving end of a dike (weir bank, arm, embankment or wall) or a curve in a weir (conch hook bend, weir bend, claw tail), fish become trapped within. In deeper water, a pool (weir eye) is constructed, and at the entrance, known as the gate (opening), a higher threshold is set so that it is difficult for fish that have entered the pool to escape.

Fishermen wearing straw sandals and carrying fishing equipment such as spears, fishing lamps, bamboo-leaf baskets, trawling nets, etc., came to make rounds of the stone weirs, and catch fish. The caught fish would be temporarily held in fish wells.

Typical structure of stone fishing weirs.

(Source / Archival Unit: National Museum of Natural Science)

Construction of Weirs Requires Collective Effort

Stone fish weirs are gigantic, complicated structures. It would be impossible to construct one alone. In the past, when setting a stone weir, a principle initiator would be chosen, and other involved parties were usually related to one another by blood or geography. With materials and manpower arranged, the next step would be to observe the tides and directions of local currents. Based on these observations, a location for the weir would be selected.

Building of weirs had to be done outside the season with high likelihood of northeastern monsoons. People transported stones by hand or with the assistance of the current. Combining the expertise and experience of all involved, the shape of the weir was gradually filled in, beginning with the main weir pool. Taking advantage of low tides, rocks were stacked to enclose an area in size ranging from a basketball court to a soccer field. Locally abundant basalt stones were used to build the bottom and sides. Then, coral and lime stone was used to fill the inner layers and seal gaps. It was a massive undertaking which was very time consuming and often took years or even decades to complete.

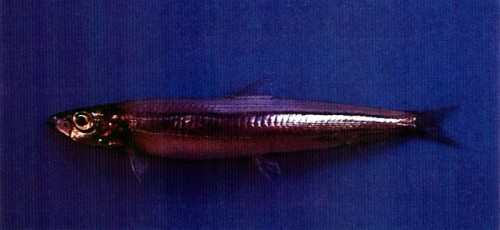

The silver-stripe round herring, a common catch in a stone fish weir.

Source / Archival Unit: Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica

Peak and Decline

The species caught in stone fish weirs were diverse. Silver-stripe round herring (Sprateolloides gracilis), Indian anchovy (Stolephorus indicus), greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili), etc., were most common. However, with gradual advancements in coastal fisheries, the advent of motorized fishing boats and the depletion of fish stocks, stone fish weirs were gradually abandoned.

References:

Jibei Stone Fish Weirs Museum

Hong Guoxiong (1999). The Stone Tidal Weirs in the Penghu Islands. Magong City, Penghu County: Penghu County Cultural Center.

Penghu Panorama Cultural Society. Installation Art in the Sea: Stone Weirs of Jibei Isle. (Tourism Bureau, MOTC, Penghu National Scenic Area, accessed Oct 30, 2009).

Li Mingru. Story of Penghu Stone Fish Weirs, Digital Archives Blog.

Yan Xiuling (1996). Spatial Organization of Fishing Activities in Chikan and Jibei. Magong City, Penghu County: Penghu County Cultural Center.

|