TELDAP Collections

| Clashes in Monga a Hundred Years Ago—Chronicles of the Gang Leaders of History |

|

Clashes in Monga a Hundred Years Ago—Chronicles of the Gang Leaders of History

In Taiwan there is a saying, “Tainan first, Lugang second, Monga third.” This phrase states that of the three major cities in Qing Dynasty in Taiwan, Monga (now Wanhua District, Taipei) was third. Monga’s proximity to the Tamsui river allowed its business activities to gradually flourish. The name “Monga,” which originated from “Moungar/Mankah” meaning canoe in the language of the local Pepo people, clearly suggests Monga was a place known for convenient shipping transportation and prosperous business development at the time.

Growing business interests gradually transformed Monga from a small village into a big city, where trade in sweet potato, wood, camphor, and so on, gradually emerged. A large number of immigrants arrived in Monga from Fujian. Naturally, new Monga residents grouped together according to where they had originally come from. However, this unintentionally sewed the seeds of “regionalist violence” to come.

Regionalist Violence—The Ding-Xia Jiao Conflict

Regionalist violence was a common phenomenon in the early days of Taiwanese society. Differing identities (ethnic, prefectural, or county origin) with the addition of competing economic interests and religious conflict, and the fact that local Qing officials were often uninterested in or incapable of managing these differences and conflicts, eventually lead to armed fighting.

In the Zhang-Quan disputes common in northern Taiwan, immigrants from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou (two prefectures in southern Fujian Province, China) engaged in armed fighting due to conflicts of interest. Even people from Quanzhou’s ‘Three Counties’ (Jinjiang, Nan’an and Hui’an) and Tongan (another county in Quanzhou), who arrived at Monga at different times, fought over rights to Monga’s wharfs. Belief in different gods also was a factor. Even the fact that Tongan was located closer to the rival Zhangzhou was seen as making Tongan people ‘too neutral’ in the disputes (not supporting the Quanzhou side). The ultimate result was the Ding-Xia Jiao Conflict.

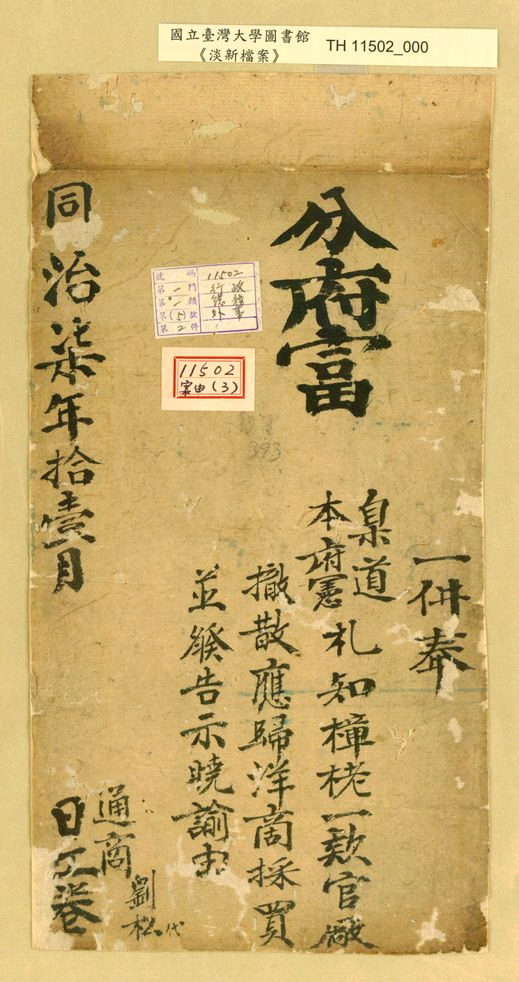

The Zhonglong Quan-Zhang ‘Harmony’ Stele, recording the frequent regionalist violence and official notices discouraging fighting and urging harmonious coexistence.

(Source: Literature and Heritage Collection, Digital Archives Project, National Taiwan University)

Business associations at that time were called Jiao. The Three Counties people, who had arrived first, formed the “Ding Jiao” (頂郊); those from Tongan, who arrived later, formed the “Xia Jiao” (廈郊 or 下郊), so-named since they conducted most of their business with Xiamen.

Since the Three Counties people settled in Monga earlier than those from Tongan, they not only controlled the wharves but also levied a 5% tax on the value of all commercial shipments, compromising the Tongan people’s business interests. This led to continuous, sporadic conflicts, and finally a large-scale outbreak of armed fighting in August 1853.

During the incident, the Tongan people’s intention to initiate the fight was snatched away by the Three Counties people, who made a preemptive attack on the Tongan base in Bajia Village (now Laosong Elementary School) via the Qingshui Zushi Temple (a center of worship for the Anxi people). Eventually, the Tongan group retreated to Dadaocheng carrying their revered Xiahai Chenghuang (an effigy of a protector god). The conflict also embroiled the Anxi people’s Qingshui Zushi Temple, which was put to the torch. Sacrifices during the incident were tragic on both sides, and a massive toll was paid by all involved.

The Longshan Temple, center of faith for the Three Counties people, is still very active today.

Qingshui Temple in Monga. Destroyed during the Ding-Xia Jiao Conflict, it was only rebuilt in 1867.

The Opening of Ports and Arrival of Foreign Traders

Eight years after the Ding-Xia Jiao Conflict, ports in Taiwan (modern day Tainan, known as Taiwan at the time) and Tamsui were opened due to the Treaty of Tianjin which the Qing government had signed with the British and French. Taiwan’s demographics became more complex; in addition to native aborigines and immigrants from the mainland, foreigners also began to arrive in Taiwan.

Of these, the principle powers were Britain and the United States, and their main goals were to do business and proselytize. They started by conducting numerous studies of Taiwan’s economy, demographics, etc., before beginning to do business in Taiwan. Camphor, in particular, carried considerable economic value at the time. Every portion of the tree was usable, and besides its use in medicines, it was also used as raw material for insect repellents, fireworks, perfume, and other products. Many foreign companies came to Taiwan to purchase this material. However, the economic behavior of these foreign companies had a considerable impact on the interests of the Han people who were already operating in Taiwan. Lack of cultural awareness led to friction and misunderstandings, and conflict gradually intensified.

Conflicts of Interest and Frequent Unrest

In 1863, the Taiwan Bingbeidao (a government post akin to the head of materiel command) instituted a government monopoly on camphor. An official camphor brokerage was established to acquire camphor at a low price and sell it to foreign companies at a high price. Seeing their own interests compromised, foreign companies were unwilling to concede. Besides formal protests, there were reports of companies secretly entering mountain areas to acquire camphor.

In April 1868, Elles & Co. of Britain had their camphor confiscated in Wuqi. The United States consul in Xiamen, Charles Le Gendre, and the British acting consul in Takao (present-day Kaohsiung), Jamieson, jointly protested, and received a tentative promise to return the camphor. In August of the same year, Elles & Co.’s agent W. A. Pickering arrived at Wuqi, intending to reclaim the confiscated camphor. However, Wuqi was not a port of trade, and the Qing government refused to issue passes to areas outside of Taiwan (present day Tainan) to foreigners. As a result, Pickering was pursued on an order by the Taiwan Bingbeidao, Liang Yuangui. Pickering fled in panic, drifting north along the coast of Taiwan to Tamsui where, according to documents, he was assisted by John Dodd.

The house formerly rented by John Dodd’s Dodd & Co. for making tea had long since been seized by the government because the owner’s taxes were in arrears. In October of the year in which Dodd assisted W. A. Pickering, the seizure order was finally lifted through coordination with the British vice-consul in Tamsui, Henry F. Holt. However, employees of Dodd & Co., holding letters and business cards from Henry F. Holt, were surrounded by nearly 500 people at the place of the rental. Dodd’s employees were accused of breaching the seizure and occupying the house, sparking a regrettable, bloody conflict.

The old Xuehai College (now Gao Family Ancestral Shrine). John Dodd’s tea factory was accused of “undermining the feng shui,” as it was nearby the college.

Due to the outbreak of the conflict, Henry F. Holt called for warships to be sent to Tamsui that night. At this moment, the Qing government still stood by the foreign companies, considering their rental to be reasonable and believing that their interests should be protected. An official document entitled “Investigation of the Case of Violation of Dodd & Co. Employees Renting Property in Monga,” issued in October of the 7th year of Emperor Tongzhi (1868), states: “Since the foreign company did not occupy the property by force, how could it so arouse the public to anger? There are many doubtful points in this case. The record is documented here for your excellence to conduct further investigation. One cannot brook the misdeeds of local ruffians, nor allow foreign enterprises to be encumbered, gradually cultivating animosity.”

Simply put, a reasonable case of property rental had turned violent, and therefore could not be as simple as it seemed. The government urged the investigator in the case, the Imperial Minister of International Trade in Shanghai, Ma Xinyi, to conduct a detailed investigation, and not allow foreign companies to become embroiled in the misdeeds of Taiwanese “ruffians”. (The documents of the Zongli Yamen—the Qing foreign ministry from 1861-1901—are archived at the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica.)

Later however, United States consul Charles Le Gendre arrived at Tamsui by gunboat, and the warships called by Henry F. Holt also arrived. Under the pressure of this military presence, Deputy Magistrate Fu Lehe from the Tamsui Office and Huwei Port Trade Committee Member Feng Qingliang countered Henry F. Holt’s demands for reparations and disciplinary action. Trying to bluff, they stated that the greater Huang family and the business people of Monga were unaware that those higher up in the Huang family clan had rented property to Dodd & Co, and they harbored discontent regarding this, since they did not identify with the private behavior of Huang household members. The two officials went so far as to attribute the event to “comprador Li Chunsheng, who commonly engaged in underhanded business practices, and was unpopular. His sly rental contract with the Huang clan and encouragement of the foreigners to occupy the property was courting trouble.” They claimed to suspect that Li Chunsheng was double-dealing illegally in his own interest.

However, the warships and gunboat were moored just at the mouth of the Tamsui river, a sight that further incited the people of Monga. Fearing that the situation would escalate, under the mediation of Charles Le Gendre the two officials finally reduced the scale of the reparations and disciplinary action and reached an albeit tenuous mutual agreement. Only Henry F. Holt perhaps obtained some political benefit, as Dodd & Co. lost their foothold in Monga, and were forced to seek new territory.

Meanwhile, the camphor disputes had escalated into a war in southern Taiwan. With the tacit approval of British acting consul John Gibson, British warships bombarded the Armory (formerly Fort Zeelandia, which was being used as an armory during this era) and invaded Anping. Shocked at this show of force, the Qing government announced the annulment of the camphor monopoly, and permitted foreigners and their employees freedom of passage.

After a series of violent attacks and counterattacks, the tension between local Taiwanese and foreigners was high. In December of that year, in a report by Ma Xinyi entitled, “Outline of the Details of the Destruction of Dodd & Co. of Britain After Renting Property in Monga, and of the Use of Military Force in Violation of Treaties by Lieutenant Gurdon,” the two events, north and south, were discussed together. The account of the Monga rental incident put Dodd & Co. in the wrong, emphasizing that the foreign company had “entered the property forcibly” and “obviously had a hidden agenda.” Thereafter, John Gibson was denounced and impeached for the “camphor war,” forcing his resignation.

An official notice from November of the 7th year of the Tongzhi Emperor (1868), announcing the abolition of government-run camphor factories and the opening of trade in camphor to foreign companies.

(Source: Literature and Heritage Collection, Digital Archives Project, National Taiwan University)

As a result of the series of riots in 1868, the Qing government lost prestige, foreigners in Taiwan shed blood, and the interests of local powers were redistributed. The collision of various preconceptions among different parties made nobody a winner. History always has something to teach us, but perhaps the greatest lesson to be learned from history is that we never learn. Perhaps more humble self-reflection and review of the stories passed down from history can provide the answer.

References:

Zongli Yamen Archive, Foreign Affairs Archives of the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica

Lu Shiqiang (September 1968), “The Case of Property Rental by Dodd & Co. of Britain in the Tongzhi Era,” Taiwan Literature, 19(3): 25-29.

|