TELDAP Collections

| The TaoTieh pattern on Chinese antiques |

|

Collection Highlight: Meet the beast! - The TaoTieh pattern on Chinese antiques

In the literary classic Zuozhuan (Zuo’s Commentary): the Eighteenth year of Emperor Wengong’s reign, a story is told like this: “Jinyun had a son who was incompetent and greedy for food, drink, wealth and all manner of luxuries. Amassing his fortune with total abandon, he enjoyed his opulent lifestyle without any thought of sharing his fortune to those in need. The people around him began to say his appetites were like those of the three ferocious beasts of the world, and called him taotie.” Ever since then, later generations have called the gluttonous, greedy or ferocious “taotie .”

Another story also claims the origin of the taotie. The beast in this story is one of Dragon’s nine sons who over-indulged in rich foods and ate endlessly. However, this apocryphal tale is much less plausible than the tale recorded in the Zuozhuan, since the legend first appears in writing later than the aforesaid text and no reference to it has been found in Chin or Han dynasty texts. Though widely repeated, one cannot take this story as a serious origin of the term taotie.

“The taotie animal pattern engraved on this ting from the Chou dynasty features heads without bodies. This fact implies that this beast had already almost devoured itself before it had the chance to swallow down human flesh.” By the time this record appeared in another literary account, Lu Chunqiu (Lu’s Spring and Autumn Annals): Chapter of the Prophets, the term taotie had become synonymous with a legendarily ferocious and gluttonous beast of yore. Thus, the engravings adorning ancient bronzes became known as “taotie engravings.”

A zun vessel, late Shang dynasty.

A common motif on bronze vessels from the Shang and Chou dynasties are bodiless beast heads. The pattern corresponds to the passage in Lu's Spring and Autumn Annals: Chapter of the Prophets in which a taotie pattern on a Chou dynasty ting is referred to as “a head without a body.” The term taotie pattern, as such, has been generally applied to all relics featuring animal face motifs.

All taotie motifs found on bronze vessels share the same basic format. The baseline of the face is formed by a raised relief of a stylized nose. On both sides of then nose are large and protruding eyes, brows, ears, and whorled horns. The pattern is strikingly symmetrical. Circular spiral and square spiral pattern often adorn the background. On some vessels, a pair of symmetrical kui dragons stand guard at either side.

A jade pendant with in the shape of an axe with taotie patterns, the Republic Era

The earliest examples of a taotie pattern (also known as the animal mask motif) in the archaeological record are found on jade ware. One example, a jade adze bearing intricately engraved taotie patterns on two sides, is most likely an artifact of the Longshan Culture. This early example was found at the Two Towns Ruins in the Rizhao city in Shandong province. Other good examples of taotie on pieces of jade ware and pottery, commonly identified with the Liangzhu culture, have been excavated downstream of the Yangtze River between Jiangsu and Zhejiang counties. Similar patterns to the taotie pattern typically seen on bronze vessels continues to appear in a great number of artifacts, notably on the gray pottery associated with the early Erlitou Culture (also known as the Xia Culture). The consistency of the both Shang and Xia’s taotie patterns has been used to prove a continuous link of history from one dynasty to the next.

The taotie pattern first appeared on bronze wares in the early Shan dynasty, and its popularity started to grow during the mid-period. The design reached its prime in the late Shan dynasty and the early Western Zhou dynasty, when it dominated the fashion and appeared as the central theme on most artifacts. In the later years of the Western Zhou dynasty, the trend of applying this pattern began to fade and the taotie started to be used mostly as a secondary or partial embellishment. By the Spring and Autumn Period, the taotie had already all but disappeared.

The designs on the bronze vessels of the Shang and Zhou dynasties feature a great variety of images, broadly categorized into either animals or the forces of nature. The animal designs are to be further subdivided into real animals and imaginary creatures: the former includes tigers, bulls, turtles and snakes, while the latter involves dragons and phoenix. The forces of nature include elemental images such as roaring fires and whirlpools. Common geometrical shapes either in regular or irregular patterns also frequently appear. The reason why the taotie pattern became one of the mainstream symbols may be that it meets the needs of the spiritual belifs or the politics for the Shang people.

Meet the beast!

Antique collections featuring the TaoTieh pattern

A jade chuan (bracelet) with animal mask and tiger skin (Serial no.7092)

Data Identification:

Serial number: 7092

Subject and Keywords: Jade

Description:

Explanatory notes: This item was crafted in a circular form. The inner rim is smooth, while the outer edge is engraved with an intricate taotie pattern. A chuan bracelet such as this was worn on the upper arm by both males and females in early ages. Over time, the accessory has evolved into an item exclusively for female use. This example is a green jade tinted grayish-brown. Simple and sophisticated, this item is a rare find with few equals.《Jade—Emblem of Traditional Chinese Virtues》

Pattern: taotie

Date:

Dynasty: the Song dynasty

Measurements:

Thickness (cm):0.6

Diameter (cm): 7.3

Gauge (cm): 6

Reference:

Denomination I of interior publishing: Collection Catalogue of National Museum of History (Vol. I):

Page: 148

Denomination II of interior publishing: Ancient Jade of China

Page: 109

Template no: 8

Denomination III of interior publishing: Jade-Emblem of Traditional Chinese Virtues

Page:30

Template no: 30

Denomination IV of interior publishing: Jade of China

Page: 46

Management rights: National Museum of History

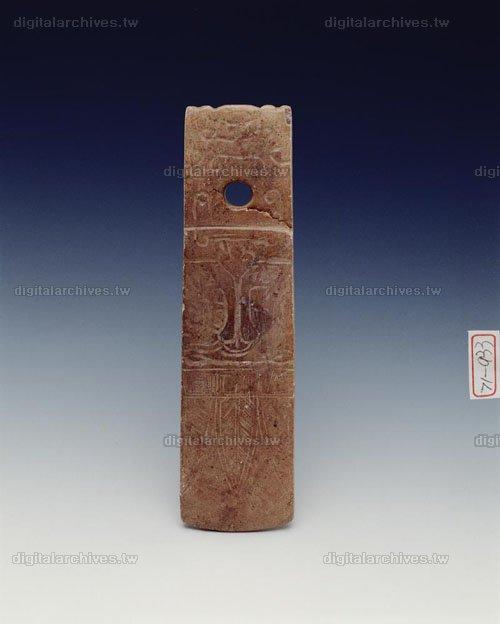

A jade yue (battle-axe) with square spiral patterns (Serial No. 7107)

Data Identification:

Serial number: 7107

Subject and Keywords: Jade

Description:

Explanatory notes: Perforated at its top, the white jade features a taotie pattern on the front and a band of square spiral patterns across the center, and is suffused with blackish-silver permeation. “Yue” emerged as a particular kind of weaponry, and later became a ritual utensil. The blade on the lower part is extraordinarily wide and curved to both sides. This design is consistent with the style and arrangement of axes crafted in the later generations.《Jade—Emblem of Traditional Chinese Virtues》

Pattern: taotie , square spiral pattern

Date:

Dynasty: The Song dynasty

Measurements:

Depth (cm): 6.9

Width (cm): 9.2

Thickness (cm): 0.7

Reference:

Denomination I of interior publishing: Collections of National Museum of History (Vol. I):

Page: 149

Denomination II of interior publishing: Ancient Jade of China

Page: 115

Template no: 65

Denomination III of interior publishing: Jade-Emblem of Traditional Chinese Virtues

Page: 61

Template no: 61

Denomination IV of interior publishing: Jade of China

Page: 98

Management rights: National Museum of History

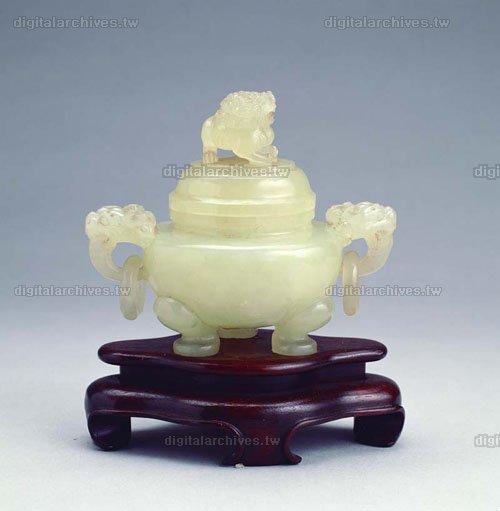

A jade incense burner (Serial no. 27374)

Data Identification:

Serial number: 27374

Subject and Keywords: Jade

Description:

Explanatory notes: This is a tripod censer with double handles crafted into two dragon-shaped loops with a ring hanging down. The lid is engraved with a raised lion-shaped button and the refined polish gives this censer a solemn touch. The surface of the item has been intentionally kept plain in order to display the warm luster of the jade. This censer is among the best ornamental artifacts related to the studies of the literati.

Pattern: taotie, circular spiral, flames

Note on the patterns: This is a tripod censer with double handles crafted into two dragon-shaped loops with a hanging ring. The lid is engraved with a raised lion-shaped button and the refined polish gives this censer a solemn touch. The surface of the item has been intentionally kept plain in order to display the warm luster of the jade. This censer is among the best ornamental artifacts related to the studies of the literati.

Date:

Dynasty: Qing

Measurements:

Depth (cm): 11.7

Width (cm): 13.7

Reference:

Denomination I of interior publishing: Collection Catalogue of National Museum of History (Vol. I)

Page: 154

Management rights: National Museum of History

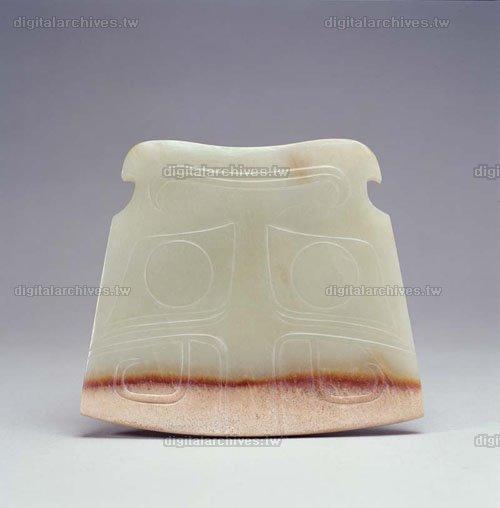

An animal mask of green jade (plaque) (Serial no. 71-00238)

Data Identification:

Serial number: 71-00238

Subject and Keywords: Jade

Description:

Explanatory notes: This item was crafted from white jade into the shape of an axe, engraved with a taotie mask on the surface. It is a forgery crafted during the Republic of China era. A plaque in jade like this is invested with an intention to dispel evil.

Pattern: animal mask

Date:

Dynasty: the Republic of China

Measurements:

Depth (cm): 11.5

Width (cm): 12.5

Reference:

Denomination I of interior publishing: Collection Catalogue of National Museum of History (Vol. I)

Page: 172

Management rights: National Museum of History

An ax-shaped jade pendant with taotie patterns (Serial no. 71-00258)

Data Identification:

Ref. no:71-00258

Date:

Dynasty:the Republic of China

Measurements:

Depth(cm): Length:4.7 Width:4.8

Management rights: National Museum of History

A green jade ax with TaoTieh patterns (Serial no. 71-00933)

Identification:

Serial number: 71-00933

Date:

Dynasty: the Republic of China

Measurements:

Depth(cm): Length:10 Width:2.5 Thickness:0.8

Management rights: National Museum of History

A bronze gu vessel

Data Identification:

Serial number:6885

Data type: Bronze ware

Subject and Keywords: Bronze ware and metalwork

Description:

Form: Gu (ancient wine vessel)

Function: Wine vessel

Technique: Piece-mold casting technique

Pattern: leaf, kui dragon animal mask, square spiral

Description: With an extremely long and narrow body and wide mouth, this gu resembled a vertical trumpet. The waist of the vessel is slightly bulged, and four strips protrude at the waist and ring foot. The ringfoot is in a step-like shape, and across the bottom are two cross perforations.

The pattern on the body is split into three parts. Long, broad leaf patterns run down from the vessel’s mouth, ending in a kui dragon pattern. Both the vessel’s waist and its ring foot have three overlapping taotie mask patterns. The entire surface is decorated with square spiral patterns. Separating the waist part and the ring foot are two raised string patterns.

Starting in the mid to late Shang dynasty, bronzes started to be cast using the suspending technique of piece-mold casting. In this process, first the bottom mold is mortised, while the sides are studded with tenons so these molds are combined. This set of tenon-mortise structure is normally in a shape of a square or a cross. The wider cross-shaped tenon found on the the ring foot of this gu vessels, help archaeologists date the object to the Shang dynasty. Some scholars suspect the cross-shaped grooves on the base of vessels could help ventilate charcoal fires that blazed just underneath when heating wine,

The ceremonial vessels now known as a gu first appear during the Sung dynasty. The term gu is applied to vessels with long cylindrical bodies with mouths in the shape of a trumpet that are supported by a high, sloping ring foot. Vol. V of Archaeological Illustrations (Kaogu Tu) records a gu vessel collected by Li of Lujiang. Based on Li’s description, this container is large enough to hold two jue vessels, which is consistent with the description of gu in Ceremony Illustrations (Li Tu), which indicated gu vessels were capable of holding two liters.

Four thick lines protrude from the belly and the ring foot of this item. These signature lines are also known as gu. One of the entries cited from the Analects of Confucius reads, “When the design of a gu vessel is changed, can we still call it a gu vessel?” Nevertheless, there is still room to debate whether this vessel is technically a gu. First, many other vessels (mostly jue) also feature protruding lines on the body. What was called a jue vessel in the Sung dynasty may not completely conform to what the Shang and West Chou dynasties considered a jue, meaning this item could be a Shang jue instead. That said, a jue may merely be a general term for a wine vessel, making classification less of a fine point.

The great bronze scholar Chen Mengjia insists in calling this a gu vessel by arguing that the word gu refers to the way the arched opening spreads to the bottom. His logic draws on the fact that in Chinese gu and arc are homophones. Regardless, the term gu has existed for a long time and continues its usage to this day.

Opinions on the function of this item are widely divided. In An Introduction to Green Bronzes in the Yin-Shang Dynasty written by Rong Geng and Zhang Weichi, the authors claim that a jue was used when wine had to be warmed before drinking, while gu was used instead if heating wasn’t necessary. This theory therefore defines the gu as a wine-drinking vessel, serving a similar function to a goblet. Yet, the scholar Hayashi Minao has argued that the gu vessels used during the mid-period of the Yin dynasty do not feature a wide opening, which is what allowed it to be used as a goblet. By the later period of the same dynasty, the vessel had evolved into a container with an extremely wide opening and a smaller belly, which reduced its capacity significantly. If used as a drinking vessel, would have been very easy for wine to spill out. Hayashi believed this proved that gu vessels were used to hold rice wine (“li”) which was then ladled out and drunk. Yili (Book of Etiquette and Cermonial): Shiguan Li (Capping rites for (the son of) a common officer) is cited as the source of Hayashi Minao’s reasoning.

Hayashi Minao’s reasoning has raised some doubts, as it seems inappropriate to interpret a container of the Yin dynasty based on documents from the Eastern Chou dynasty. Still, one is able to take the assertion for reference. This opinion has been quoted by the later generations to then postulate that gu vessels were used as shakers.

Judging from excavated antiques, the bronze gu vessels were first used during the period represented in the upper stratum of the Erligang Site, which lifted gu usage to its prime in the Yin dynasty before it declined in the early period of the Western Chou dynasty. By the mid-period of the Western Chou dynasty, gu vessels all but disappear from the archaeological record.

Reference: 朱鳳翰 (Zhu Fenghan),《古代中國青銅器》(The ancient Chinese bronzes)。郭寶鈞(Guo baojun),《商周青銅群綜合研究》《Collective Studies of Bronze ware in the Shang and Zhou Dynasties》。

Date: Later period of the Shang dynasty

Measurements: Gauge 8.3X height 29.5

Domain: Chinese

Management rights: National Museum of History

A bronze gong vessel

Data Identification:

Serial number: 6910

Data type: Bronze ware

Subject and Keywords: Bronze ware and metalwork

Description:

Form: Zun

Function: Wine vessel

Technique: Piece-mold casting technique

Pattern: Phoenix, animal mask, bead linked in a continuous pattern

Description: The wide opening is the most distinctive feature of this zun vessel. The trumpet-shaped gauge of the opening is wider than those of its belly or foot. The vessel's long neck ends in a short shoulder that slopes into a wider rim before bulging into a wide dome shape that then tapers down towards the base. The vessel ends in a step-like high ring foot.

Below the vessel’s shoulder, the round bulge feature distorted animal designs that link dramatic, protruding eyes and huge mouths in a continuous band. Three sets of symmetrical taotie patterns (animal masks) are decorate on the surface of the belly, while two protruding lines have been molded around the neck. Two square perforations were set in the ring foot.

Starting in the mid to late Shang dynasty, bronzes started to be cast using the suspending technique of piece-mold casting. In this process, first the bottom mold is mortised while the sides are studded with tenons so these molds are combined. This set of tenon-mortise structure is normally in a shape of a square or a cross. The wider square-shaped tenon found on the ring foot of this gu vessels, help archaeologists date the object to the Shang and late Shang dynasty. Some scholars suspect that the square-shaped grooves on the base of vessels could help ventilate charcoal fires that blazed just underneath when heating wine.

What is generally called a zun vessel features a wide opening, a wide and round belly, a high ring foot and a wider body. Some zun do not have any inscriptions. According to the recorded inscriptions taken from bronze vessels, the usage of the term zun (in its original version,?尊) is not dissimilar to that of yi, which are sacrificial vessels. Wang Guowei thus refers to zun as a “great common name” for many different artifacts which were used in sacred rites. The fact that the word zun has been used to describe wine vessels in general does not help clarify the issue. It was in the Song dynasty that the word zun first became used to describe a genuine container. That being established, neither inArchaeological Illustrations nor Catalog of Abundant Antiques can one find an exact standardization of the zun vessel. Rong Geng argues in his book A General Study of Yi Vessels in the Shang and Zhou Dynasties that “Nowadays, any vessels that resemble large gu or zhi get termed zun.” Rong Geng’s text marks the first instance where gu, zhi, hu and lei are officially distinguished from zun, making the term a distinct and specific class of bronze vessels. Though disagreement exists as to the technical definition, scholars agree that zun were used as wine containers from the Song dynasty onwards. This vessel was in its prime of popularity from the Shang dynasty to the middle period of the Western Zhou dynasty.

Reference: 朱鳳翰(Zhu Fenghan),《Ancient Chinese Green Bronze Ware》。郭寶鈞(Kuo baoju),《商周Bronze Ware Collective Studies》。

Measurements: gauge 31.5

Domain: Chinese

Management rights: National Museum of History

A bronze yue (battle-axe)

Data Identification:

Serial number:7801

Data type: Bronze ware

Subjects and Keywords: Bronze ware and metalwork

Description:

Form: Yue

Function: Weaponry

Technique: Piece-mold casting technique

Pattern: taotie, animal mask

Description: Featuring an animal mask and coated with verdigris, this item was based on earlier stone ax designs but features a thicker blade than its stone forbearers.

Date: The later period of the Shang dynasty

Measurements:

Length: 22.8X width: 17

Domain: Chinese

Management rights: National Museum of History

A ding vessel

Data Identification:

Serial number:30158

Data type: Bronze ware

Subject and Keywords: Bronze ware and metalwork

Description:

Form: Ding

Function: Cooking appliance

Technique: Piece-mold casting technique

Pattern: Cidada and taotie

Description: This ding, or li ding, has a deep, sack-like belly, three narrow columns for legs, a pair of handles, and separate molds. Each part of the ding’s belly is decorated with a taotie pattern. A band of cicada patterns is engraved near the opening, while square spiral patterns form the background. All three column legs are decorated with intricate cicada patterns. Inside the vessel were two-character inscription, ya (亞) and peng (倗). The entire surface of this vessel is coated with patina.

In the Shuowen jiezi (An Explication of Written Characters), a ding vessel is defined as “With three legs and double handles, the ding vessel meant to hold treasures of the five flavors and tastes. Once charcoal has been placed underneath and burnt, the vessel can serve as a cooking pot.” Scholars agree on the definition, description, and usage of ding. A ding vessel most frequently serves as a cooking vessel. Several excavated ding vessels have been found with residue from smoke and charcoal on their bottoms and legs, which confirms its use for meal preparation. However, during banquets, ding vessels were used as serving dishes for meat or seasoning.

Most ding vessels have three legs, a pair of handles, and a deep belly with solid molding inside. The tall, stable column legs were designed to accommodate a charcoal fire underneath, while the handles were for carrying. Among bronze wares from the Shang and Zhou dynasties, more ding vessels survive than any other type, and ding have the highest profile and greatest recognition.

Aside from its use as a household utensil among the nobles, the ding vessel was one of the most important objects used in rites and ceremonies, such as formal banquets and sacrificial rituals. The Chinese classics state that “the bell’s ring signals for the people to begin dining, and ding vessels are set in a row to serve the food.” This record demonstrates the symbolic importance of the bell and ding during rites and ritual concerts.

Ding vessels have also become an emblem of royal power. According to the record of Zuozhuan, in the third year of Xuan Gong, King Zhuang of Chu seized power in the Central Plains. In the record of this major event borrows the character for ding and uses it as a metaphor for the ascension of King Zhuang of Chu. So it seems that ding vessels holds an important and special position in the ancient society.

Reference:

朱鳳翰(Zhu Fenghan) Ancient Chinese Green Bronze ware

郭寶鈞(Guo Baojun) Collective Studies of Bronze ware in the Shang and Zhou Dynasties

Date: The later period of the Shang dynasty

Measurements: Gauge 16.5 X height 20.2

Domain: Chinese

Management rights: National Museum of History

|