TELDAP Collections

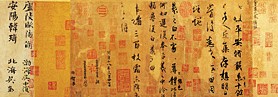

| Three Passages: P'ing-an, Ho-ju, and Feng-chü |

|

Wang Hsi-chih (ca. 303-361), Chin Dynasty (265-420) This scroll includes three works by Wang Hsi-chih mounted together. All are tracing copies done before the T'ang dynasty (618-907), but they were so faithfully done that they still reveal the speed and variety of brushwork, even where the brush turned and was lifted up. In other words, the lines appear to have a life of their own. They depart from the formal qualities of ancient clerical script and take the art of calligraphy to a realm of freedom that clearly expresses the individuality of the artist, which is why Wang became revered as the "Sage Calligrapher". Starting from the 6th century AD, emperors have sought the letters of such famous calligraphers as Wang Hsi-chih for their collection. In the past, it was the custom to mount authentic letters from the hands of masters into handscrolls. When passed down through the generations, however, they were often cut apart and remounted in different formats. This is a rare example of this ancient mounting style. All three works in this scroll are precise copies of short letters by Wang Hsi-chih done by outlining the strokes and dots, then filling them with ink. The first four lines at the right represent the first work, “P'ing-an”. Calligraphed in both running and cursive script, the letter mentions "Hsiu-ts'ai", a cousin of Wang Hsi-chih. The next letter “Ho-ju”, composed of three full lines of characters and appearing in the middle of the scroll, was done in running script. In this letter, Wang sends greetings to the recipient and an account of recent days. The last letter is “Feng-chü” and appears as two lines to the left. Composed in running script, it was a letter to accompany a gift of oranges to a friend. This last piece was particularly famous in the T'ang dynasty. Of the three, the brush movement in “P'ing-an”, in terms of application and lifting of the brush from the paper, is quite varied. Ho-ju, on the other hand, is slightly more regulated. In “Feng-chü”, the characters also exhibit considerable variety. The result is a range of expression, from a flowing brush to a cutting knife.

|